Teaching is a Skill

Last updated on 2025-10-02 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I improve my teaching?

Objectives

- Use peer-to-peer lesson practice to transform your instruction.

- Give thoughtful and useful feedback.

- Incorporate feedback into your teaching practices.

So far, we have focused on how we can be effective instructors by understanding how people learn and how to create a positive classroom environment, covering two of our primary goals in helping you become a certified Carpentries Instructor. Now our focus will shift to developing additional teaching skills that you can use in a Carpentries workshop setting, starting with the process of “lesson study”, or teaching observation and feedback.

Lesson Study: Applying a Growth Mindset to Teaching

We have seen that providing opportunities for practice and giving useful feedback to learners are essential components in the learning process. Learning to teach is no different.

However, many people assume that teachers are born, not made. From politicians to researchers and teachers themselves, most reformers have designed systems to find and promote those who can teach and eliminate those who cannot. As Elizabeth Green describes in Building a Better Teacher, though, that assumption is wrong, which is why educational reforms based on it have repeatedly failed.

To assume that teaching is an “inherited” or innate skill is to take on a fixed mindset about teaching. A growth mindset believes that anyone can become a better teacher by the same methods we use to learn any subject – reflective practice. More specifically, instructors develop teaching skill over time through practice and improve most when given feedback on their performance from other instructors who share their pedagogical model.

We know that teachers can learn how to teach because of research done on the Japanese method of jugyokenkyu or “lesson study.”

In the 1980s and 90s, an educational psychologist named James Stigler observed teachers in the US and Japan. In the OECD’s annual rankings of countries’ educational achievements, Japanese students routinely test near the top in reading, math and science, while American students rank at or below average.

Looking at differences in teaching methods, Stigler found that American teachers met at most once a year to exchange ideas about teaching, compared to the weekly or even daily meetings of Japanese teachers. During these meetings, teachers in the US described their lessons to each other, but they did not observe each others’ teaching in practice. In contrast, Japanese teachers regularly conducted lesson study: observing each other at work, discussing the lesson afterward, and studying curriculum materials with their colleagues.

The situation is different in many English-language school systems: in the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, and elsewhere, where often what happens in the classroom stays in the classroom. Teachers are not able to watch each other’s lessons on a regular basis, so they cannot borrow each other’s good ideas. The result is that every teacher has to invent teaching on their own. They may get lesson plans and assignments from colleagues, the school board, a textbook publisher, or the Internet, but each teacher has to figure out on their own how to combine that with the theory they have learned in their educational programs to deliver an actual lesson in an actual classroom for actual learners. When teachers do not observe each other teaching, the tricks and techniques that each instructor has painstakingly incorporated into their practice do not have the opportunity to spread, limiting forward momentum on system-wide improvements to teaching.

Therefore, just like other disciplines (sports and music are two good examples), teachers benefit from closely observing the work of others. The Carpentries pedagogical model supports lesson study by providing many opportunities for our instructors to learn from each other. In this training, you will have opportunities to practice teaching for one another and to give each other feedback. You will also have the opportunity to practice in front of an experienced instructor as part of your instructor training checkout. In addition, Carpentries Instructors always teach in pairs (or more), giving you the opportunity to learn by observing and to get feedback from your fellow instructors.

Reading It Is Not Enough

Several research studies (in 2007, 2012, and 2015) have shown that teachers do not adopt instructional practices based on reports about the effectiveness of those practices. Social norms, institutional culture, and lack of time and support prevent many teachers from moving out of their accustomed teaching habits. Change in teaching does not come about through reading about new teaching practices, but by seeing these practices in action, practicing them and getting feedback from other instructors.

Feedback Is Hard

Sometimes it can be hard to receive feedback, especially negative feedback.

Feedback is most effective when the people involved share ground rules and expectations. In Carpentries teaching, we use the 2x2 paradigm for feedback. Each person giving feedback is expected to provide at least one piece of negative and one piece of positive feedback each for content and delivery. This helps overcome two common tendencies when giving feedback on teaching: to focus on the content (even though delivery is at least as important) and to either provide only negative or only positive feedback.

Here is a list of different ways that you can set the stage for receiving or providing feedback in a way that facilitates growth.

Initiate feedback. Most people will not offer it freely, and those who do are not the only voices you should listen to. Also, it is easier to hear feedback that you have asked for.

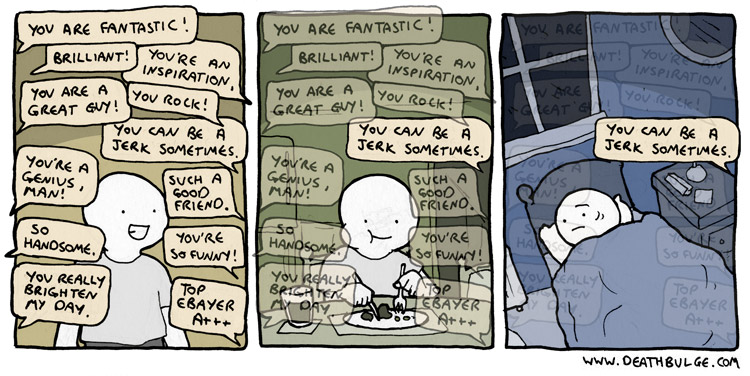

Be specific. See a great example of this from this Lunar Baboon comic.

As an instructor one way to get specific feedback is to provide questions that focus the responses. Writing your own feedback questions allows you to frame feedback in a way that is helpful to you - the questions below reveal what did not work in your teaching, but read as professional suggestions rather than personal judgments. For example:

“What is one thing I could have done as an instructor to make this lesson more effective?”

“If you could pick one thing from the lesson to go over again, what would it be?”

-

Balance positive and negative feedback.

- Ask for or give “compliment sandwiches” (one positive, one negative, one positive)

- Ask for both types of feedback, and give both types.

Provide a clear next step with negative feedback to follow that will help the recipient improve.

Communicate expectations. If your teaching feedback is taking the form of an observation (and you are comfortable enough with the observer), tell that person how they can best communicate their feedback to you.

When giving feedback, remember that giving and receiving feedback is a skill that requires practice, so do not be frustrated if your feedback is rejected but try to think about why the recipient might not have been comfortable with the feedback you gave.

Use a feedback translator. Have a fellow instructor (or other trusted person in the room) read over all the feedback and give an executive summary. It can be easier to hear “It sounds like most people are following, so you could speed up” than to read several notes all saying, “this is too slow” or “this is boring”.

This is part of the reason for The Carpentries rule, “Never teach alone.” Having another Instructor in the classroom divides the effort, but more importantly, it is a chance for Instructors to learn from one another and be a supportive voice in the room.

Finally, be kind to yourself. If you are a self-critical person, it is OK to remind yourself:

- The feedback is not personal. In many cases, feedback says more about the person giving it than the person receiving it.

- There are always positives along with the negatives. Save your favourites to review regularly!

Giving Feedback

We will start by observing some examples of teaching and providing some feedback.

Watch this example teaching video as a group and then give feedback on it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jxgMVwQamO0.

English and Spanish captions are available by clicking the settings icon in the video.

Put your feedback in the Etherpad. Organise your feedback along two axes: - positive vs. opportunities for growth (sometimes called “negative”) and - content (what was said) vs. presentation (how it was said).

This exercise should take about 10 minutes.

Now that you have had some practice observing teaching and giving feedback, let us practice with each other.

Using Feedback

Look back at the feedback you received on your teaching. How do you feel about this feedback? Is it fair and reasonable? Do you agree with it?

Identify at least one specific change you will make to your teaching based on this feedback. Describe your change in the Etherpad.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Hopefully you were able to identify at least one helpful comment in the feedback you received and are able to use it to start (or continue) the process of improving your teaching. Remember, teaching is a skill that is learned. If you notice yourself feeling hurt or threatened by the feedback you got, or rejecting it as unfair or wrong, pause and try to consider the feedback from a growth mindset - that through practice and feedback, your skills are going to improve. By strengthening your growth mindset with respect to teaching, you can transform getting feedback from an unpleasant experience to a richly rewarding one. You will have more opportunities to practice teaching and to get and give feedback in parts 3 and 4.

- Like all other skills, good teaching requires practice and feedback.

- Lesson study is essential to transferring skills among teachers.

- Feedback is most effective when those involved share ground rules and expectations.