Content from Welcome

Last updated on 2025-11-13 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is The Carpentries and how do we approach teaching?

- What should you expect from this training?

Objectives

- Identify common ground with some of your fellow participants.

- Understand a general structure and core goals of The Carpentries.

- Predict what will and will not be covered in this training.

- Know where to find The Carpentries Code of Conduct and how to report an incident.

In an online training, ensure that captions are turned on, that one trainer claims host, and that the host adds other trainers as co-hosts. The host key is in the email to trainers from the core team prior to the training.

Pronouns and Names

Using correct names and pronouns (e.g. “she/her”) is important for setting a respectful tone. Learning these is hard to do quickly, so we recommend displaying it prominently during the training.

In an online training, give everyone a moment to update their display name to reflect how they would like to be addressed.

At an in-person event, we recommend supplying name tags and markers, or using plain paper to create table-displayed name placards.

Note that pronouns are personal and some participants might prefer not to share them. Do not force people to share their pronouns. One reason to avoid pressuring people to share them is to allow people to share their gender identity only when they feel ready to. It is, however, necessary for all participants to use pronouns and names as listed when participants provide them.

The resources below can provide additional guidance on respectful pronoun usage:

- The proper use of pronouns in language: https://lgbt.ucsf.edu/pronounsmatter

- The importance of using pronouns: https://www.pronouns.org/

- How to use personal pronouns: https://www.pronouns.org/how

- How to deal with situations when you use the wrong pronoun: https://www.pronouns.org/mistakes

Before The Course Begins

There are multiple ways to build a sense of community early in an instructor training event and help ensure participants engage fully with one another. Some example activities are:

- Include an icebreaker question in the sign-in section or separately on the etherpad

- Invite participants to share their names (and optionally pronouns) verbally and/or share their icebreaker answers

- Model informal chat as participants come into the room on Day 1, particularly if a number of participants are early or late

Hearing participants say their own names is especially valuable in online workshops with diverse participants whose names may be difficult for some trainers and instructor trainees to pronounce.

When planning icebreakers and introductions, it’s important to be aware of time considerations, given the number of participants and expected timing. Balancing what is done in the etherpad and verbally can help, as can avoiding activities that are likely to encourage longer introductions or extended interaction at this point.

Getting to know each other

If the Trainer has chosen an icebreaker question, participate by writing your answers in the Etherpad.

Code of Conduct

To make clear what is expected, everyone participating in The Carpentries activities is required to abide by our Code of Conduct. Any form of behaviour to exclude, intimidate, or cause discomfort is a violation of the Code of Conduct. In order to foster a positive and professional learning environment we encourage you to:

- Use welcoming and inclusive language

- Be respectful of different viewpoints and experiences

- Gracefully accept constructive criticism

- Focus on what is best for the community

- Show courtesy and respect towards other community members

If you believe someone is violating the Code of Conduct, we ask that you report it to The Carpentries Code of Conduct Committee by completing this form.

Introductions

Hello everyone, and welcome to The Carpentries instructor training. We are very pleased to have you with us.

This Event’s Trainers

To begin class, each Trainer should give a brief introduction of themselves.

(For some guidelines on introducing yourself, see some content from the Introductions section later in the training.)

Now, we would like to get to know all of you.

Reviewing The Carpentries Experience and Goals

For the multiple choice questions below, please place an “X” next to the response(s) that best apply to you. Then find yourself a spot in the Etherpad below to write a short response to the last question.

Have you ever participated in a Software Carpentry, Data Carpentry, or Library Carpentry Workshop?

- Yes, I have taken a workshop.

- Yes, I have been a workshop helper.

- Yes, I organised a workshop.

- No, but I am familiar with what is taught at a workshop.

- No, and I am not familiar with what is taught at a workshop.

Which of these most accurately describes your teaching experience?

- I have been a graduate or undergraduate teaching assistant for a university/college course.

- I have not had any teaching experience in the past.

- I have taught a seminar, workshop, or other short or informal course.

- I have been the primary or responsible teacher for a university/college course.

- I have taught at the primary or secondary education level.

- I have taught informally through outreach programs, hackathons, libraries, laboratory demonstrations, and similar activities.

Why are you taking this course? What goals do you have for this training?

This exercise should take about 5 minutes for responses, with an optional 10 for additional discussion as time permits.

To make sure everyone has the same context, we will give a brief overview of The Carpentries organisation before starting the training.

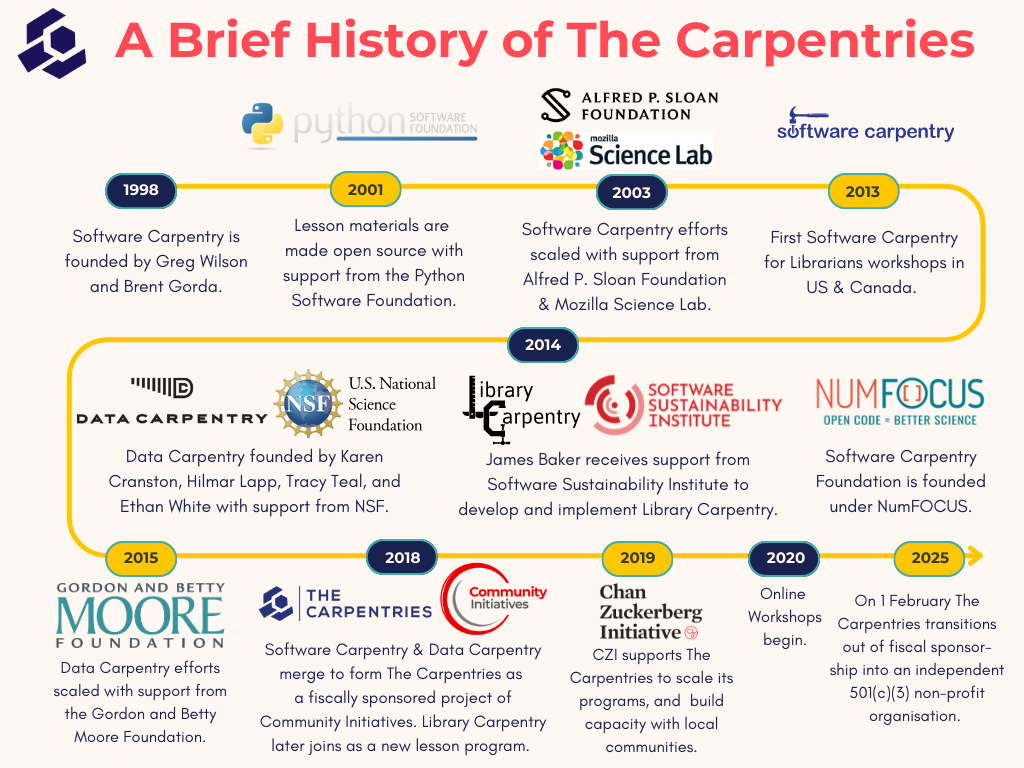

A Brief Overview of The Carpentries

Software Carpentry, Data Carpentry, and Library Carpentry are official Lesson Programs of The Carpentries. The Carpentries is a global community of volunteer researchers, educators, and others oriented around improving basic computing and data skills for researchers through intensive, short-format workshops.

- Software Carpentry focuses on helping researchers develop foundational computational skills

- Data Carpentry focuses on helping researchers work effectively with their data through its lifecycle

- Library Carpentry focuses on teaching data skills to people working in library- and information-related roles.

The main goal of The Carpentries is not to teach specific skills, per se - although those are covered - but rather, to convey best practices that will enable researchers to be more productive and do better research.

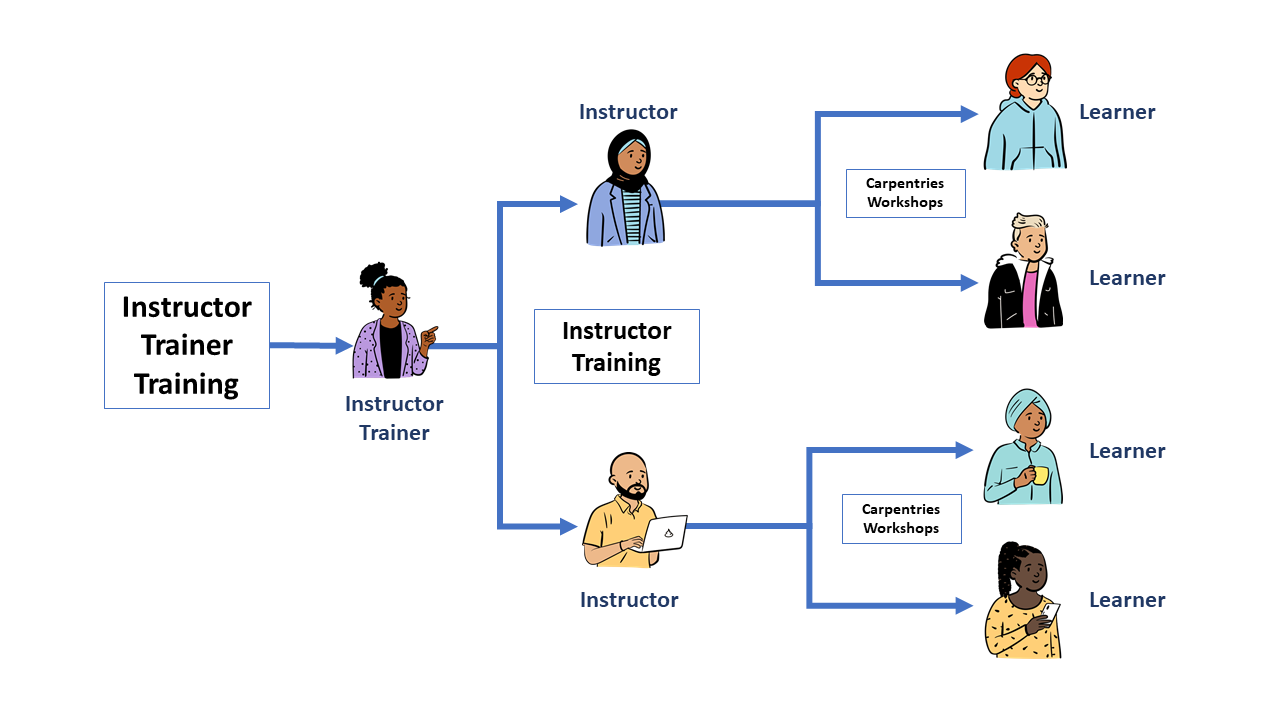

Instructor Training Overview

The goal of this training is to provide you with the skills and information you need to become a certified Carpentries Instructor. Our expectations of certified Instructors is that they:

- be familiar with and understand how to apply research-based teaching principles, especially as they apply to The Carpentries audience.

- understand the importance of a respectful and inclusive classroom environment; commit to creating such an environment; and be able to identify and implement The Carpentries policies and general practices to accomplish this.

- practice and develop skills in the teaching methods used in The Carpentries workshops.

- learn enough about The Carpentries organisation to know where to go for help, how to start organizing a workshop, and how to get involved with community activities.

These four goals are broken down into four main themes of content:

How Learning Works

One of our main emphases will be discussing the best practices of teaching. We will be introducing you to a handful of key educational research findings and demonstrating how they can be used to help people learn better and faster.

Building Teaching Skill

Just like learning a new language, a musical instrument, or a sport, teaching is a skill that requires practice and feedback. We will have many opportunities to practice and give each other feedback throughout this training.

Creating a Positive Learning Environment

One part of making this a productive experience for all of us is a community effort to treat one another with kindness and respect. The Code of Conduct is one piece of this. We will also be discussing and practicing teaching techniques to create a positive and welcoming environment in your classrooms, and will spend some time talking about why this is important.

The Carpentries History and Culture

In addition to the teaching practices and philosophy that have been adopted by The Carpentries community, it is helpful to become familiar with our community structure and organisational procedures as you prepare to join our Instructor community. The greatest asset of The Carpentries is people like you - people who want to help researchers learn new skills and share their own experience and enthusiasm. Meeting your fellow trainees and Instructor Trainers at this event is your first step into The Carpentries community.

What We Leave Out

We will not be going over Data Carpentry, Library Carpentry, or Software Carpentry workshop content in detail (although you will gain familiarity with some of the content through the exercises), This training is a significant requirement for becoming a certified Carpentries Instructor. The additional steps for certification, called Checkout, will require that you dig into the workshop content yourself. We will talk about checkout requirements more in part 3 of this training.

We also do not discuss how to develop lessons, although we do mention some aspects of lesson design. We include this information to help you as an instructor identify the important components of lessons for high impact, inclusive teaching. The Carpentries now has a growing subcommunity dedicated to lesson development, and offers additional training in lesson development.

If there is a particular topic that you would like us to address, let the Trainers know.

What Questions Do You Have?

We hope and expect that you will have many questions during this training! Please do not keep them to yourself. If you find something unclear, chances are good that others will have the same question, too. It is ok to ask even if you think you might have missed an answer already given (e.g. during a distracted moment or a dropped connection)! Depending on the time available, your Trainers may ask you to share your questions verbally, in the Etherpad, or otherwise.

Now that we have a road map of what we are covering we are ready to begin our training. Our goal is that by the end, you will have acquired some new knowledge, confidence, and skills that you can use in your teaching practice in general and in teaching Carpentries workshops specifically.

- The Carpentries is a community of practice. We strive to provide a welcoming environment for all learners and take our Code of Conduct seriously.

- This episode sets the stage for the entire training. The introductions and exercises help everyone begin to develop a relationship and trust.

- This training will cover evidence-based teaching practices and how they apply specifically to The Carpentries.

- Learner motivation and prior knowledge vary widely.

Content from Building Skill With Practice

Last updated on 2025-08-05 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 60 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do people learn?

- Who is a typical Carpentries learner?

- How can we help novices become competent practitioners?

Objectives

- Compare and contrast the three stages of skill acquisition.

- Identify a mental model and an analogy that can help to explain it.

- Apply a concept map to explore a simple mental model.

- Understand the limitations of knowledge in the absence of a functional mental model.

- Create a formative assessment to diagnose a broken mental model.

We will now get started with a discussion of how learning works. We will begin with some key concepts from educational research and identify how these principles are put into practice in Carpentries workshops.

The Carpentries Pedagogical Model

The Carpentries aims to teach computational competence to learners. We take an applied approach, avoiding the theoretical and general in favour of the practical and specific. By showing learners how to solve specific problems with specific tools and providing hands-on practice, we develop learners’ confidence and lay the foundation for future learning.

A critical component of this process is that learners are able to practice what they are learning in real time, get feedback on what they are doing, and then apply those lessons learned to the next step in the learning process. Having learners help each other during the workshops also helps to reinforce concepts taught during the workshops.

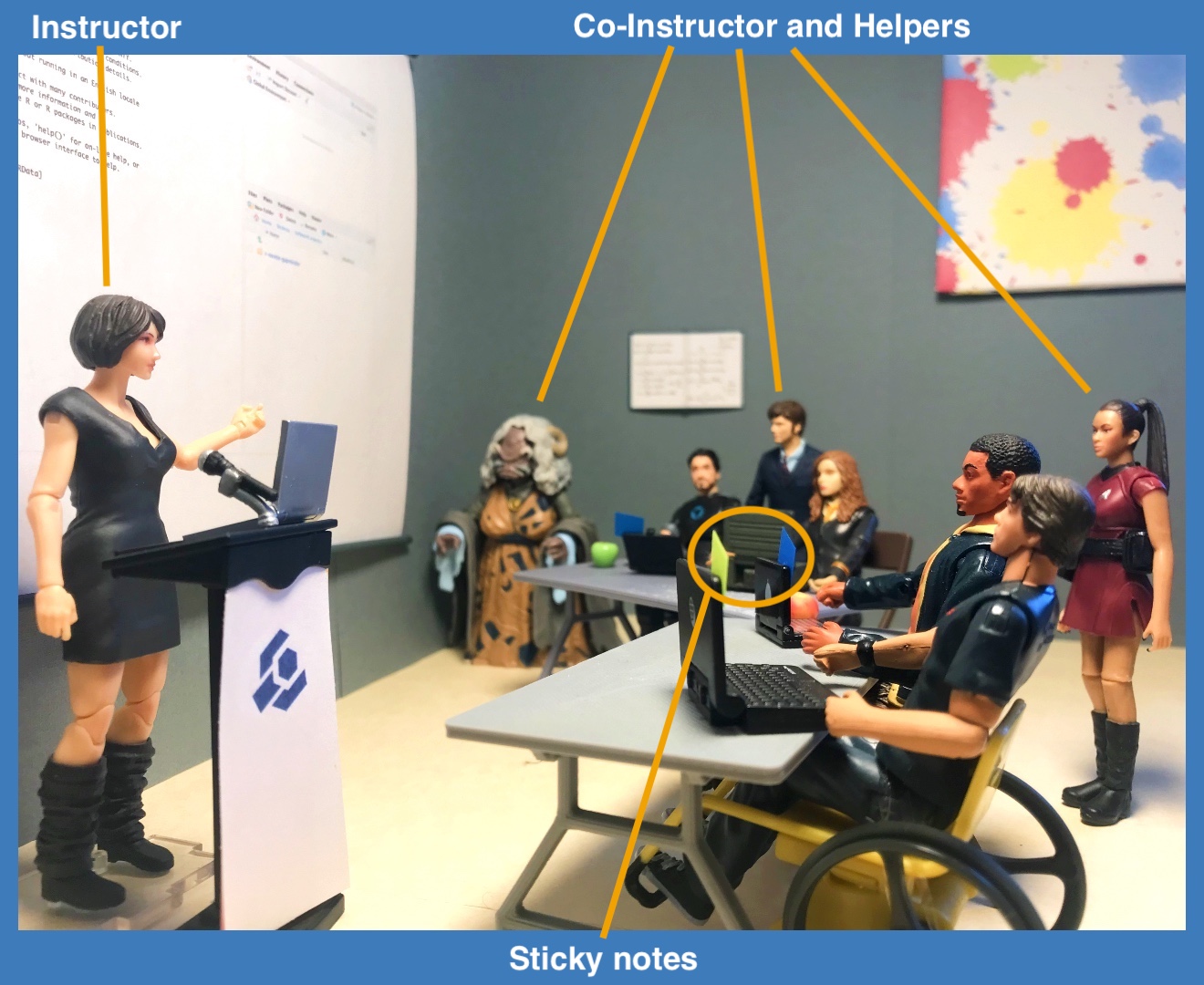

A Carpentries workshop is an interactive event – for learners and instructors. We give and receive feedback throughout the course of a workshop. We incorporate assessments within the lesson materials and ask for feedback on sticky notes during lunch breaks and at the end of each day.

One reason why practice and feedback are so important is because a Carpentries workshop is not simply a source of information: It is the starting point for development of a new skill. To understand what this means, we will start by exploring what research tells us about skill acquisition and development of a “mental model.”

The Acquisition of Skill

Our approach is based on the work of researchers like Patricia Benner, who applied the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition in her studies of how nurses progress from novice to expert (see also books by Benner). This work indicates that through practice and formal instruction, learners acquire skills and advance through distinct stages. In simplified form, three stages of this model are:

-

Novice: someone who does not know what they do not know, i.e., they do not yet know what the key ideas in the domain are or how they relate. Novices may have difficulty formulating questions, or may ask questions that seem irrelevant or off-topic as they rely on prior knowledge, without knowing what is or is not related yet.

Example: A novice learner in a Carpentries workshop might never have heard of the bash shell, and therefore may have no understanding of how it relates to their file system or other programs on their computer.

-

Competent practitioner: someone who has enough understanding for everyday purposes. They will not know all the details of how something works and their understanding may not be entirely accurate, but it is sufficient for completing normal tasks with normal effort under normal circumstances.

Example: A competent practitioner in a Carpentries workshop might have used the shell before and understand how to move around directories and use individual programs, but they might not understand how they can fit these programs together to build scripts and automate large tasks.

-

Expert: someone who can easily handle situations that are out of the ordinary.

Example: An expert in a Carpentries workshop may have experience writing and running shell scripts and, when presented with a problem, immediately sees how these skills can be used to solve the problem.

Note that how a person feels about their skill level is not included in these definitions! You may or may not consider yourself an expert in a particular subject, but may nonetheless function at that level in certain contexts. We will come back to the expertise of the Instructor and its impact – positive and negative – on teaching, in the next episode. For now, we are primarily concerned with novices, as this is The Carpentries’ primary target audience.

It is common to think of a novice as a sort of an “empty vessel” into which knowledge can be “poured.” Unfortunately, this analogy includes inaccuracies that can generate dangerous misconceptions. In our next section, we will briefly explore the nature of “knowledge” through a concept that helps us differentiate between novices and competent practitioners in a more useful and visual way. This, in turn, will have implications for how we teach.

Building a Mental Model

Models are not perfect but are still helpful

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

- George Box, statistician

Understanding is never a mirror of reality, even for an expert; rather, it is an internal representation based on our experience with a subject. This internal representation is often described as a mental model. A mental model allows us to extrapolate, or make predictions beyond and between the narrow limits of experience and memory, filling in gaps to the point that things “make sense.”

As we learn, our mental model evolves to become more complex and, most importantly, more useful. A useful model makes reasonable predictions and fits well within the range of things we are likely to encounter. While there will always be inaccuracies – or “misconceptions” – these do not interfere with day-to-day functioning. A useful model does not seize up or break down entirely as new concepts are added.

The power (and limitations) of analogies

Some mental models can be succinctly summarised by comparison to something else that is more universally understood. Good analogies can be extraordinarily useful when teaching, because they draw upon an existing mental model to fill in another, speeding learning and making a memorable connection. However, all analogies have limitations! If you choose to use an analogy, be sure its usefulness outweighs its potential to generate misconceptions that may interfere with learning.

Analogy Brainstorm

- Think of an analogy to explore. Perhaps you have a favourite that relates to your area of professional interest, or a hobby. If you prefer to work with an example, consider this analogy from education: “teaching is like gardening.”

- Share your analogy with a partner or group. (If you have not yet done so, be sure to take a moment to introduce yourself, first!) What does your analogy convey about the topic? How is it useful? In what ways is it wrong?

This activity should take about 10 minutes.

Analogies at Work: “Software Carpentry”

People often ask where our name came from. Greg Wilson has this to say:

“Brent Gorda and I came up with the name in 1998 to differentiate what we were teaching from software engineering. That’s about digging the Channel Tunnel; we’re about the computational equivalent of hanging drywall.”

The word “carpentry” acts as a metaphor – a type of analogy – inspiring a comparison with something concrete, hands on, practical, and useful. This clearly conveys the purpose of our organisation: to support computational skill development among working practitioners who need the right tools and practices to be effective day to day.

A mental model may be represented as a collection of concepts and facts, connected by relationships. The mental model of an expert in any given subject will be far larger and more complex than that of a novice, including both more concepts and more detailed and numerous relationships. However, both may be perfectly useful in certain contexts.

Returning to our example levels of skill development:

- A novice has a minimal mental model of surface features of the domain. Inaccuracies based on limited prior knowledge may interfere with adding new information. Predictions are likely to borrow heavily from mental models of other domains which seem superficially similar.

- A competent practitioner has a mental model that is useful for everyday purposes. Most new information they are likely to encounter will fit well with their existing model. Even though many potential elements of their mental model may still be missing or wrong, predictions about their area of work are usually accurate.

- An expert has a densely populated and connected mental model that is especially good for problem solving. They quickly connect concepts that others may not see as being related. They may have difficulty explaining how they are thinking in ways that do not rely on other features unique to their own mental model.

Mapping a Mental Model

People often request to see more examples of concept maps. These are some examples linked from a previous version of the curriculum:

- Array Math

- Conditionals

- Creating and Destroying Files

- Sets and Dictionaries in Python

- Input and Output

- Lists and Loops

- Git Version Control

Most of these are much larger than our recommended limit for the activity. It can be helpful to make a larger map and then narrow down to a smaller one.

Most people do not naturally visualise a mental model as a diagram of concepts and relationships. Mental models are complicated! Yet, visual representation of concepts and relationships can be a useful way to explore and understand hidden features of a mental model.

There are certain ways in which you may routinely use visual organisers, such as flow charts or biochemical pathway diagrams. A more general tool that is useful for exploring any network of concepts and relationships is a concept map. Pioneered for classroom use by John Novak in the 1970s, a concept map asks you to identify which concepts are most relevant to a topic at hand and – critically – to identify how they are connected. It can be quite difficult to identify and organise these connections! However, the process of forcing abstract knowledge into a visual format can force you to name connections that you might otherwise have quietly assumed, or illuminate gaps that you may not have been aware of. Especially where analogies are not available, concept mapping can help you to make your mental model of a concept more clear to yourself or others.

As an example, consider a mental model of the relationship between a small ball and water in a full glass.

The concept map below illustrates a simple mental model that a young child might develop after putting the ball in the water.

Give a child balls of three different sizes, and they might put together a somewhat more complex mental model, perhaps illustrated as:

Mapping a Mental Model

- On a piece of paper, draw a simplified concept map of the same concept you discussed in the last activity, but this time without the analogy. What are 3-4 core concepts involved? How are those concepts related?

If you would like to try out an online tool for this exercise, visit Excalidraw at https://excalidraw.com.

- In the Etherpad, write some notes on this process. Was it difficult? Do you think it would be a useful exercise prior to teaching about your topic? What challenges might a novice face in creating a concept map of this kind?

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Misconceptions

The mental model above connects a ball to the water it can displace, recognizing that ‘more’ ball can move ‘more’ water. This mental model is perfectly functional for a child who wants to have fun splashing water around. It may endure in this way for several years of beaches and bathtubs.

However, when this child is asked to predict what would happen to the water if a ball were not bigger or smaller but heavier or lighter, they will naturally apply their existing mental model to the task. BUT…

What a surprise! The challenge presented by this new information is that it clashes with the pre-existing mental model, to which it seemed to apply. This prior knowledge needs to be adjusted to a new understanding that incorporates the difference between properties of mass and volume.

When mental models break, learning can occur more slowly than you might expect. The longer a prior model was in use, and the more extensively it has to be unlearned, the more it can actively interfere with the incorporation of new knowledge. Our child may quickly adapt to this new information if they had never thought much about mass before and were simply trying out an existing mental model on a new situation. However, if they had extensive experience with balls that were both larger and heavier (for example), it may take longer to unlearn what they thought they understood about mass.

Most mental models worth mapping are not so simple. Yet, forcing complex ideas in to this simplified format can be useful when preparing to teach, because it forces you to be explicit about exactly what concepts are at the heart of your topic, and to name relationships between them.

Types of Misconceptions

Correcting learners’ misconceptions is at least as important as presenting them with correct information. There are many ways of classifying different types of misconceptions. For our purposes, it is useful to consider 3 broad categories:

- Simple factual errors. These exist in isolation from any deeper understanding. These are the easiest to correct. Example: believing that Vancouver is the capital of British Columbia.

- Broken models. These occur when inaccuracies explain relationships and generate predictions (often successfully!) in an existing mental model. These take time to address, demanding that learners reason carefully through examples to see contradictions. Examples: believing that motion and acceleration must always be in the same direction, or that seasons are related to the shape of the earth’s orbit.

- Fundamental beliefs, which are deeply connected to a learner’s social identity and are the hardest to change. Examples: “the world is only a few thousand years old” or “human beings cannot affect the planet’s climate”. “I am not a computational person” may, arguably, also fall into this category of misconception.

The middle category of misconceptions is the most useful type to watch out for in Carpentries workshops. While teaching, we want to expose learners’ broken models so that we can help them begin to deconstruct them and build better ones in their place.

Anticipating Misconceptions

Describe a misconception you have encountered as a teacher or as a learner.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Using Formative Assessment to Identify Misconceptions

In order to effectively root out pre-existing misconceptions that need to be un-learned and stop quietly developing misconceptions in their tracks, an Instructor needs to be actively and persistently looking for them. But how?

Like so many challenges we will discuss in this training, the answer is feedback. In this case, we want feedback that allows us to assess the developing mental model of a trainee in highly specific ways, to verify that learning is proceeding according to plan and not careening off in some unpredicted direction. We want to get this feedback while we teach so that we can respond to that information and adapt our instruction to get learners back on track.

This kind of assessment has a name: it is called formative assessment because it is applied during learning to form the practice of teaching and the experience of the learner. This is different from exams, for example, which sum up what a participant has learned but are not used to guide further progress and are hence called summative.

Feedback from formative assessment illuminates misconceptions for both Instructors and learners. It also provides reassurance on both sides when learning is proceeding on track! It is far more reliable than reading faces or using feelings of comfort as a metric, which tends to be what Instructors and learners default to otherwise.

Formative Assessments

Any instructional tool that generates feedback that is used in a formative way can be described as “formative assessment.” Based on your previous educational experience (or even this training so far!) what types of formative assessments do you know about?

Write your answers in the Etherpad; or go around and have each person in the group name one.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Formative assessments can serve many purposes other than hunting down misconceptions, such as verifying engagement or supporting memory consolidation. We will discuss some of these functions in later episodes. In this section, we are interested quite narrowly in evaluating mental models.

One example of formative assessment that can be used to tease out misconceptions is the multiple choice question (MCQ). When designed carefully, these can target anticipated misconceptions with surgical precision. For example, suppose we are teaching children multi-digit addition. A well-designed MCQ would be:

Q: what is 27 + 15 ?

a) 42

b) 32

c) 312

d) 33The correct answer is 42, but each of the other answers provides valuable insight.

Identify the Misconceptions

Choose one wrong answer and write in the Etherpad what misconception is associated with that wrong answer. This discussion should take about 5 minutes.

- If the child answers 32, they are throwing away the carry completely.

- If they answer 312, they know that they cannot just discard the carried ‘1’, but do not understand that it is actually a ten and needs to be added into the next column. In other words, they are treating each column of numbers as unconnected to its neighbors.

- If they answer 33 then they know they have to carry the 1, but are carrying it back into the same column it came from.

Each of these incorrect answers has diagnostic power. Each answer looks like it could be right: silly answers like “a fish!” offer therapeutic comedy but do not provide insight; nor do answers that are wrong in random ways. “Diagnostic power” means that each of the wrong choices helps the instructor figure out precisely what misconceptions learners have adopted when they select that choice.

Formative assessments are most powerful when:

- all learners are effectively assessed (not only the most vocal ones!) AND

- an instructor responds promptly to the results of the assessment

An instructor may learn they need to change their pace or review a particular concept. Using formative assessment effectively to discover and address misconceptions is a teaching skill that you can develop with reflective practice.

Handling Outcomes

Formative assessments allow us as instructors to adapt our instruction to our audience. What options do we have if a majority of the class chooses:

- mostly one of the wrong answers?

- mostly the right answer?

- an even spread among options?

Choose one of the above scenarios and compose a suggested response to it in the Etherpad.

This discussion should take about 5 minutes.

- If the majority of the class votes for a single wrong answer, you have a widespread misconception and can stop to examine and correct that misconception.

- If most of the class votes for the right answer, it is ok to explain the answer and move on. Helpers can make themselves available to assist anyone who still feels uncertain.

- If answers are pretty evenly split between options, learners may be guessing randomly, reflecting an absent mental model rather than a broken one. In this case it is a good idea to go back to a point where everyone was on the same page.

Designing a few MCQs with diagnostic power is useful when preparing to teach even if they are never used, for the same reason that concept mapping can be useful: it forces the instructor to think about the learners’ mental models and try to anticipate how they might be broken. In short, it helps Instructors to put themselves into the learners’ heads and see the topic from their point of view. We will talk more about the process of preparing to teach in a later episode.

The Importance of Going Slowly

It takes work to actively assess mental models throughout a workshop; this also takes time. This can make Instructors feel conflicted about using formative assessment routinely. However, the need to conduct routine assessment is not the only reason why a workshop should proceed more slowly than you think.

One key insight from research on cognitive development is that novices, competent practitioners, and experts each need to be taught differently. In particular, presenting novices with a pile of facts early on is counter-productive, because they do not yet have a model or framework to fit those facts into. In fact, presenting too many facts too soon can actually reinforce an incorrect mental model. (This is a key problem with the “empty vessel” analogy described earlier.)

Most learners coming to Carpentries lessons are novices, and do not have a strong mental model of the concepts we are teaching. Thus, our primary goal is not to teach the syntax of a particular programming language, but to help them construct a working mental model so that they have something to attach facts to. In other words, our goal is to teach people how to think about programming and data management in a way that will allow them to learn more easily on their own or understand what they might find online.

If someone feels it is too slow, they will be a bit bored. If they feel it is too fast, they will never come back to programming. — Kunal Marwaha, SWC Instructor

If our goal is to help novices construct an accurate and useful mental model of a new intellectual domain, this will impact our teaching. For example, we principally want to help learners form the right categories and make connections among concepts. We do not want to overload them with a slew of unrelated facts, as this will be confusing.

An important practical implication of this latter point is the pace

at which we teach.

In the first main episode of Software Carpentry’s lesson on the Unix

shell, which covers “Navigating Files and Directories”, there are

only four “commands” for 40 minutes of teaching. Ten minutes per command

may seem glacially slow, but that episodes’s real purpose is to teach

learners about paths; later on, they will learn about history,

wildcards, pipes and filters, command-line arguments, redirection, and

all the other big ideas on which the shell depends, and without which

people cannot understand how to use commands.

That mental model of the shell also includes things like:

- Anything you repeat manually, you will eventually get wrong (so let

the computer repeat things for you by using tab completion and the

historycommand). - Lots of little tools, combined as needed, are more productive than a handful of programs. (This motivates the pipe-and-filter model.)

These two examples illustrate something else as well. Learning consists of more than “just” adding information to mental models; creating linkages between concepts and facts is at least as important. Telling people that they should not repeat things, and that they should try to think (by analogy) in terms of little pieces loosely joined, both set the stage for discussing functions. Explicitly referring back to pipes and filters in the shell when introducing functions helps solidify both ideas.

Meeting Learners Where They Are

One of the strengths of Carpentries workshops is that we meet learners where they are. Carpentries Instructors strive to help learners progress from whatever starting point they happen to be at, without making anyone feel inferior about their current practices or skillsets. We do this in part by teaching relevant and useful skills, building an inclusive learning environment, and continually getting (and paying attention to!) feedback from learners. We will be talking in more depth about each of these strategies as we go forward in our workshop.

- Our goal when teaching novices is to help them construct useful mental models.

- Exploring our own mental models can help us prepare to convey them.

- Constructing a useful mental model requires practice and corrective feedback.

- Formative assessments provide practice for learners and feedback to learners and instructors.

Content from Part 1 Break

Last updated on 2024-03-11 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 0 minutes

Take a break. If you can, move around and look at something away from your screen to give your eyes a rest.

Content from Expertise and Instruction

Last updated on 2025-10-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Does subject expertise make someone a great teacher?

- How are we (as Instructors) different from our learners and how does this impact our teaching?

Objectives

- Explain what differentiates an expert from a competent practitioner.

- Describe at least two examples of how expertise can help and hinder effective teaching.

- Identify strategies for becoming aware of your expert awareness gap.

- Demonstrate strategies for avoiding dismissive language.

Examining Your Expertise

In the last episode, we discussed the transition from novice to competent practitioner through formation of a functional mental model. We now shift our attention to experts. The expert we want to talk about is you!

Even if you do not yet think of yourself as an expert, you may nonetheless have advanced to the point where some of these key characteristics – and potential pitfalls – apply to you. We will discuss what distinguishes expertise from novices/competent practitioners, how being an expert can make it more difficult to teach novices, and some tools to help instructors identify and overcome these difficulties.

What Makes an Expert?

An earlier topic described a key difference between novices and competent practitioners. Novices lack a mental model, or have only a very incomplete model with limited utility. Competent practitioners have mental models that work well enough for most situations. How are experts different from both of these groups?

What Is An Expert?

What is something that you are an expert in? How does your experience when you are acting as an expert differ from when you are not an expert?

This discussion should take about 5 minutes.

Some points to touch on in discussion: - the feeling of expertise as an instructor vs practitioner - the difference between expert knowledge in the topic and expertise in communicating about the topic

In reviewing the answers to the question above you will find that the expert experience amounts to much more than just knowing more facts. Competent practitioners can memorise a lot of information without any noticeable improvement to their performance. So, what makes an expert? The answer is that experts have more connections among pieces of knowledge that help them think and problem-solve quickly; more “short-cuts”, if you will.

This brings us back to our mental model diagrams, where facts are nodes and relationships are arcs. The greater connectivity of a mental model allows experts to:

- see connections between two topics or ideas that no one else can see

- see a single problem in several different ways

- know how to solve a problem, or “what questions to ask”

- jump directly from a problem to its solution because there is a direct link between the two in their mind. Where a competent practitioner would have to reason “A therefore B therefore C therefore F”, the expert can go from A to F in a single step (“A therefore F”).

We will expand on some of these below and how they can manifest in the way you teach.

Expertise and Teaching

Because your learners’ mental models will likely be less densely connected than your own, a conclusion that seems obvious to you will not seem that way to your learners. It is important to explain what you are doing step-by-step, and how each step leads to the next one.

Mind The Gap

The problem with this is that when you are used to going from A to F in a single leap, it can be very hard to remember that novices need to go through steps B and C before they can understand the connection between A and F. Experts are frequently so familiar with their subject that they can no longer imagine what it is like to not understand the world that way. This phenomenon is known in the literature as an expert blind spot.

Expert Awareness Gap

In The Carpentries, we aim to create an inclusive environment. We prefer to refer to this phenomenon as the expert awareness gap to be consistent with our objective to use inclusive language. It can be exclusionary to use a term that relates to a disability for other purposes. We introduce both terms, however, to help you as future instructors engage with these ideas in the literature and with people outside of The Carpentries community.

In evaluating potential terms, one instructor provided the following thoughts:

I like expert awareness gap because it is more precise than blind spot (it is not about seeing, but about noticing) and feels more of a surmountable challenge than a disadvantage. To me a disadvantage can sometimes feel like a thing that exists as a fact, like an inevitable consequence, but a gap is a thing to be bridged– and we certainly want instructors to try to overcome (or mitigate) their expert awareness gap

Awareness gaps can lead to some interesting reversals in the classroom. While deep expertise in a subject area can be valuable when teaching, it can also create obstacles that must be overcome with practice. People with less expertise, who still remember what it is like to have to learn the things, can be better equipped to anticipate novice misconceptions compared with an expert who has not learned to identify their awareness gaps.

What does this mean for you? If you have deep expertise in the subject you are hoping to teach, listen carefully to your learners, and seek out less-expert colleagues to discuss your teaching plans. If, on the other hand, you still feel new to your subject area – perhaps you even feel a little tentative about whether you are “expert enough” to teach – take heart! Your explanations may be more likely to meet novice learners where they are.

Awareness Gaps

Choose one of the following two prompts to write about in the etherpad:

- Is there anything you are learning how to do right now? Can you identify something that you still need to think about, but your teacher can do without thinking about it?

- Think about the area of expertise you identified for yourself earlier. What could a potential awareness gap be?

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Switching Language

If you worked in the USA in the same building as something called a “delicatessen”, you might invite a friend to meet you at “the deli” or simply at “the restaurant” and expect them to know what you mean, because you naturally use these terms interchangeably. Yet, someone less familiar with US English might hesitate, wondering if these words mean the same thing, or close enough, under the circumstances. Similarly, in a Carpentries workshop, an Instructor may start a workshop talking about “Unix”, but then automatically start using words like “Bash” and “shell” without noticing that learners are struggling to figure out how these two new words are related.

Novice learners can be confused by interchangeable use of more than just vocabulary. In programming, multiple forms of notation may be used to reference a column in a data frame, for example, with the same effect. Instructors may use absolute file paths in one place, then default to relative file paths elsewhere without noticing that explanation is required. Or, they may assume that a learner who has an absolute file path will be able to navigate to the file in a GUI.

What do you use interchangeably?

In the Etherpad, share an example of words or notation that you sometimes use to accomplish or refer to the same thing. If possible, try to think of an example that might occur in a Carpentries workshop.

Building awareness of how you can represent the same concept in multiple different ways will help you avoid doing so without explanation while teaching.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

What Problem?

Experts are also better at diagnosing errors than novices or competent practitioners. If faced with an error message while teaching, an expert will often automatically diagnose and solve a problem before a novice has even finished reading the error message. Because of this, it is very important while teaching to be explicit about the process you are using to engage with errors, even if they seem trivial to you, as they often will.

Diagnosis

What is an error message that you encounter frequently in your work? (These are often syntax errors.) Take a few minutes to plan out how you would explain that error message to your learners. Write the error and your explanation in the Etherpad.

This discussion should take about 5 minutes. (Optionally, this may be discussed in group breakouts, adding 5 minutes.)

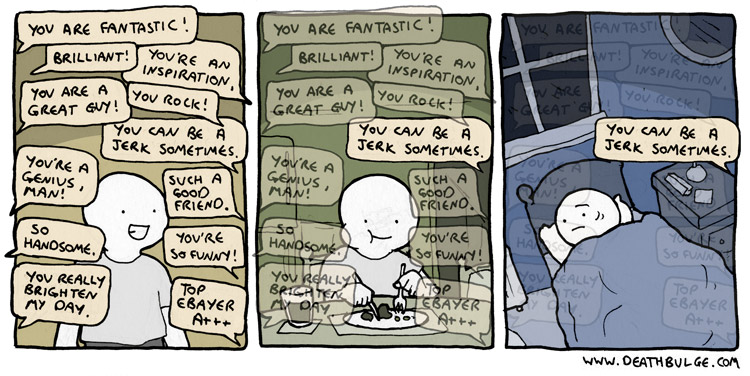

“Just” and Other Dismissive Language

Instructors want to motivate learners! We will talk more about motivation in a later episode. But here, we will take a moment to recognise one ineffective strategy often deployed by experts who want learners to believe that a task is as easy as they think it is. This often manifests in using the word “just” in explanations, as in, “Look, it is easy, you just… (wave magic wand with undecipherable incantations)” This language gives learners the very clear signal that the person helping them thinks their problem is trivial and that there must be something wrong with them if they do not experience it that way.

With practice, we can change the way we speak to avoid dismissive language and replace it with more positive and motivating word choices.

Changing Your Language

- What other words or phrases, besides “just”, can have the same effect of dismissing the experience of finding a subject difficult or unclear?

- Propose an alternate phrasing for one of the suggestions above.

Write your examples and alternatives in the Etherpad.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

It is hard to break the habit of trying to convince learners that a task is “easy”! A few alternatives might include statements like:

- “This task will become really easy once you have learned how to do it.”

- “We only need to learn two new commands to accomplish the next task.”

- “This task may feel like it will take you all year to learn, but in my experience it will take you a lot less time than that to master it.”

“Any Questions?”

Another well-intended move that can go wrong in the presence of awareness gaps is the call for questions. An Instructor may accidentally dismiss learner confusion by asking for questions in a way that reveals that they do not actually expect that anyone will have them. Asking, “Does anyone have any questions?” implies that most people will not; the shorter the wait time before moving on, the more this implication is magnified. Instead, consider asking “What questions do you have?” and leaving a healthy pause for consideration. This firmly establishes an expectation that people will, indeed, have questions, and should challenge themselves to formulate them.

You Are Not Your Learners

As you seek to re-acquaint yourself with the novice experience, it can be tempting to think back to your own experiences getting started in programming. Trips down memory lane can be productive! However, it is important that you take care not to generalise from your experience to that of your novice learners.

We will talk more about knowing your audience in a later episode. For now, here are two points to keep in mind when contemplating the learner experience:

- In most cases a researcher’s primary goal is not to learn programming, but to do better and more efficient research. They may not wish to take the time to learn how fundamental syntax or data structures work, or to learn any ‘fun facts’ that are not strictly necessary; they just want to know how to get their work done. This does not mean they never will be interested – maybe this is how you got your start, too! But if you began with an interest in programming, keep in mind that this can make their learning experience very different from yours.

- Some researchers have avoided learning programming previously because they believe that the time investment will be excessive and will interfere with their other work. These kinds of beliefs can make their motivation to persevere more fragile than yours might have been when you got started.

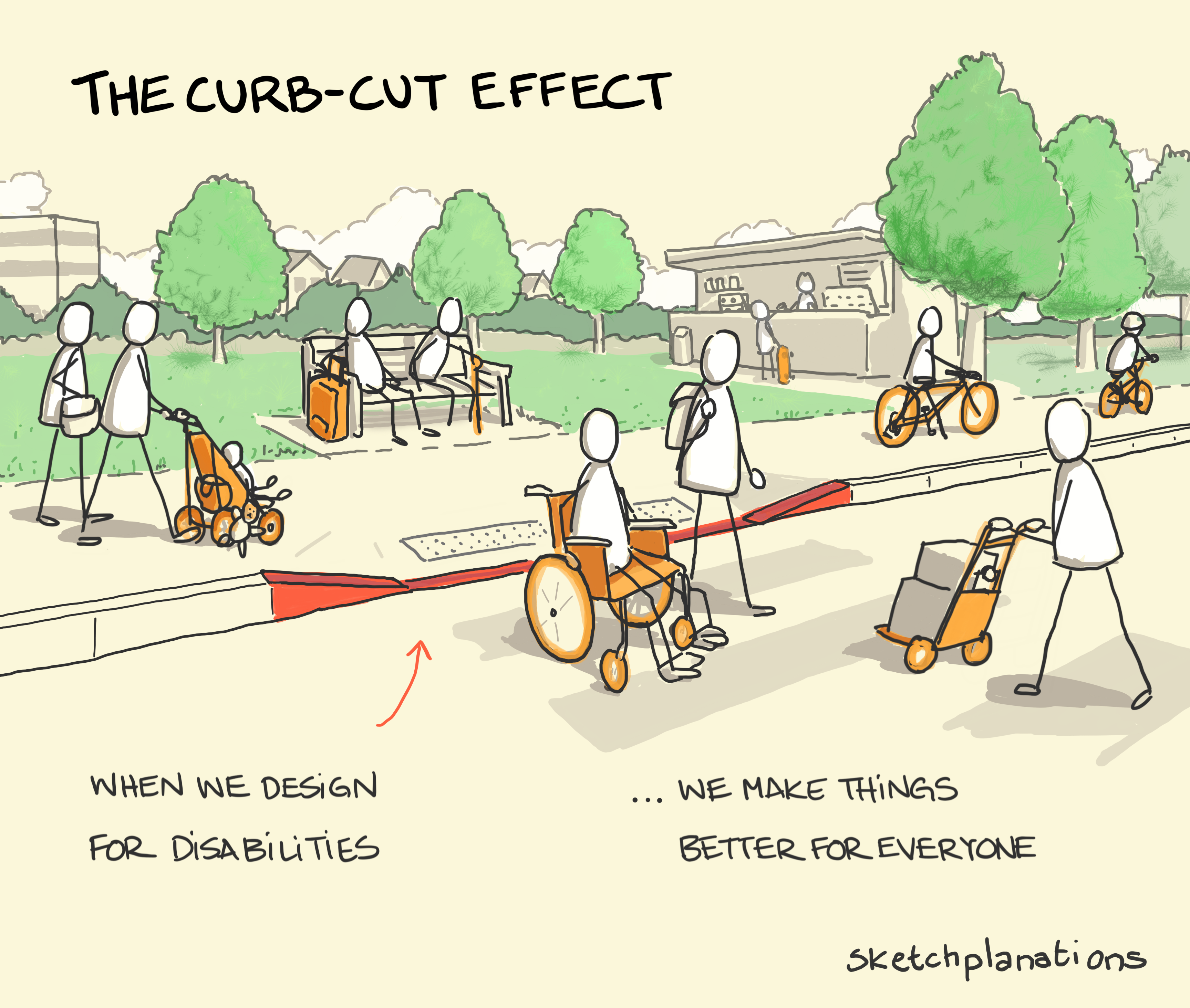

The Carpentries Is Not Computer Science

Many of the foundational concepts of computer science, such as computability, are difficult to learn and not immediately useful. This does not mean that they are not important, or are not worth learning, but if our aim is to convince people that they can learn this stuff, and that doing so will help them do more research faster, computer science concepts are less compelling than things like automating repetitive tasks.

Expert Advantages

As we have seen, the high connectivity of an expert’s mental model poses challenges while teaching novices. However, that is not to say that experts cannot be great teachers! Because of their well-connected knowledge, self-aware experts are well-poised to help students make meaningful connections, to confidently turn an error into a learning opportunity, or to explain a complex topic in multiple ways. Experts can be highly effective as long as they learn to identify and correct for their own expert awareness gaps. Whether or not you identify as an expert, we hope this episode has started you on the path toward developing that skill.

The Importance of Practice (Again)

How can you make sure that expert awareness gaps are not negatively affecting your workshop? Keep in touch with your learners through frequent formative assessment! If you stumble into an expert awareness gap, create confusion by using interchangeable terms, or accidentally discourage rather than invite questions, formative assessment has the power to bring these problems to the surface. As you develop teaching skill, you may be able to avoid these pitfalls. Until then, becoming aware of when they occur will help you to keep their impact under control.

- Experts face challenges when teaching novices due to expert awareness gaps.

- Things that seem easy to us are often not experienced that way by our learners.

- With practice, we can develop skills to overcome our expert awareness gaps.

Content from Memory and Cognitive Load

Last updated on 2026-02-05 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is cognitive load and how does it affect learning?

- How can we design instruction to work with, rather than against, memory constraints?

Objectives

- Remember the quantitative limit of human memory.

- Distinguish desirable from undesirable cognitive load.

- Evaluate cognitive load associated with a learning task.

In our final topic in how people learn (and therefore, how we can be more effective instructors), we will be learning more about human memory: specifically, how to remove unnecessary “load” in order to facilitate learning.

Types of Memory

Learning involves memory. For our purposes, human memory can be divided into two different layers. The first is called long-term. It is where we store persistent information like our friends’ names and our home address. It is essentially unbounded (barring injury or disease, we will die before it fills up) but it is slow to access.

Our second layer of memory is called short-term. This is the type of memory you use to actively think about things and is often called working memory. It is much faster, but also much smaller: in 1956, George Miller estimated that the average adult’s short-term memory could hold 7±2 items for a few seconds before things started to drop out. This is why phone numbers are typically 7 or 8 digits long: back when phones had dials instead of keypads, that was the longest sequence of numbers most adults could remember accurately for as long as it took the dial to go around and around.

More recent research suggests that short-term memory is actually even smaller than this. Regardless of its exact size, which may differ across people and contexts, we know that short-term memory is limited. This has important implications for teaching. If we present our learners with large amounts of information, without giving them the opportunity to practice using it (and thereby transfer it into long-term memory), they will not retain the material as well as if we present small amounts of information interspersed with practice opportunities. This is yet another reason why going slowly and using frequent formative assessment is important.

For a semi-anonymous alternative to having learners write their score in the etherpad on the challenge below, you can create a list with numbers and have people add X’s. This also makes it easier to see the score distribution.

Example:

Test Your Working Memory

Try a short test of working memory at https://miku.github.io/activememory/.

What was your score? If you are comfortable, share your answer in the Etherpad.

If you are unable to use this activity, ask your Trainer to implement the analog version of this test.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Test Your Working Memory - Analog version (5 min)

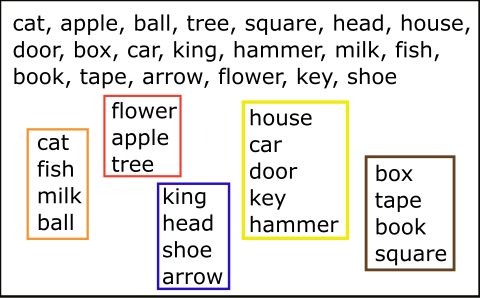

Read the following list and try to memorise the items in it:

cat, apple, ball, tree, square, head, house, door, box, car, king, hammer, milk, fish, book, tape, arrow, flower, key, shoe

Without looking at the list again, write down as many words from the list as you can. How many did you remember? Write your answer in the Etherpad.

Most people will have found they only remember 5-7 words. Those who remember less may be experiencing distraction, fatigue, or (as we will learn shortly) “cognitive overload.” Those who remember more are almost invariably deploying a memory management strategy.

Strategies For Memory Management

Because short-term memory is limited, we can support learners by not flooding their short term memory with too many separate pieces of information. Does this mean we should teach fewer concepts? Yes! However, this is not the only tool in our toolbox. We can also assist by providing strategies and exercises to help them form the connections that will a) support them in holding more things in short-term memory at once and b) begin to consolidate some concepts, moving them into long-term memory.

Chunking

Our minds can store larger numbers of facts in short-term memory by creating chunks, or relationships among separate items, allowing them to be remembered as a single item. For example, most of us will remember a word we read as a single item (“cat”), rather than as a sequence of letters (“c-a-t”). Similarly, the pattern made by five spots on cards or die is remembered as a whole rather than as five separate pieces of information.

Improving Short-term Memory with Chunking

Repeat the memory exercise you did earlier, but this time, try to form short stories or phrases, or a visual image, from the words you see.

Write the number of words you remembered in the Etherpad. How does this compare with your first attempt?

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Associating concepts reduces the number of effective items in your short-term memory, allowing you to keep more information in your head at once.

You may have come across other mnemonic strategies, including some that rely on imagining a “place” association for each item, e.g. a “memory palace.” While slightly different from chunking, this is another example of how connecting information can make it easier to remember.

Using Formative Assessment to Support Memory Consolidation

Formative assessment is a key component in helping learners solidify their understanding and begin transferring ideas into long-term memory. Why? Because it engages the brain in retrieving recently-learned information and actively applying it to solve a problem. This helps to both reinforce and connect that new information in useful ways.

The limitations of short-term memory are one reason why assessments should be frequent: short-term memory is limited not only in space, but also in time. If you wait too long before deploying a formative assessment, some of the information necessary to complete the task will already be forgotten. This time window can be very short, especially if a lot of content is being taught at once! Be sure to remind learners about prior concepts essential to a task. When you no longer need to remind them, this is a sign that your efforts in supporting memory consolidation have worked!

Group Work

Elaboration, or explaining your work, supports transfer to long-term memory. This is one reason why teaching is one of the most effective ways to learn! Group work can feel uncomfortable at first and consumes time in a workshop, but learners often rate group work as a high point for both enjoyment and learning in a workshop. This is also a great opportunity for helpers to circulate and address lingering questions or engage with more advanced discussions.

Opportunities for Reflection

Reflection is another tool that can help learners review things they have learned, strengthen connections between them, and consolidate long-term memories. Like formative assessment, asking learners for feedback can double as both a source of information and an effective consolidating prompt, as providing feedback demands some reflection on what has been learned. We will talk more about methods for this in the next section. You may also wish to pause and allow learners to write summary notes for themselves or otherwise ask them to review what they have learned at various points in the workshop.

Limit concepts

In the same vein as “going slowly,” it is important to limit the number of concepts introduced in a lesson. This can be hard! As you are reviewing a lesson to teach, you will doubtless come across related concepts that are very useful, and you may feel strongly motivated to sneak them in. Planning your lesson with a concept map can help you not only identify key concepts and relationships, but also to notice when you are trying to teach too many things at once.

Attention is a Limited Resource: Cognitive Load

Memory is not the only cognitive resource that is limited. Attention is constrained as well, which can limit the information that enters short term memory in the first place as well as interfere with attempts at consolidation. While many people believe that they can “multi-task,” the reality is that attention can only focus on one thing at a time. Adding items that demand attention adds more things to alternate between attending to, which can reduce efficiency and performance on all of them.

The Theory of Cognitive Load

There are different theories of cognitive load. In one of these, Sweller posits that people have to attend to three types of things when they are learning:

- Things they have to think about in order to perform a task (“intrinsic”).

- Mental effort required to connect the task to new and old information (“germane”).

- Distractions and other mental effort not directly related to performing or learning from the task (“extraneous”).

Cognitive load is not always a bad thing! There is plenty of evidence that some difficulty is desirable and can increase learning. However, there are limits. Managing all forms of cognitive load, with particular attention to extraneous load, can help prevent cognitive overload from impeding learning altogether.

One way to manage cognitive load as tasks become more complex is by using guided practice: creating a structure that narrowly guides focus on specific skills and knowledge in a stepped fashion, with feedback at each step before transferring attention to a new feature.

Is Guided Practice “Hand Holding?”

An alternative to guided practice is a minimal guidance approach, where learners are given raw materials (for example a text or reference) and asked to explore and learn to solve problems on their own. Minimal guidance is commonly found in many instructional strategies you may have encountered, variously known as constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential or inquiry-based learning.

These strategies are not without merit! Indeed, they can work exceptionally well with advanced learners. However, they frequently fall flat, especially with novice audiences. A landmark paper by Kirshner et al. responds to the popularity and uneven success of minimal guidance, applying cognitive load theory to understand why these strategies often fail.

Some people feel concerned that guided practice amounts to “hand-holding,” implying that learners who receive support may never learn to function independently. This view fails to account for the additional cognitive load experienced by novices creating new connections while learning a task. Minimally-guided instruction requires learners to simultaneously master a domain’s factual content AND its search and problem-solving strategies. Fostering creativity and independence takes time. Minimal guidance is intuitively appealing, but that does not mean it always works.

Mapping Cognitive Load

Look in the curriculum that you chose to prepare for this training and focus on one step or task that learners will be asked to complete.

- What concepts will learners need to understand and hold in short-term memory in order to complete this task?

- Draw a concept map connecting these concepts. What relationships do learners need to understand to connect them?

- How many of these concepts and relationships have been introduced since the previous step or exercise?

With a partner or in small groups, discuss what you have found. Are your learners at risk of cognitive overload at this point in your workshop? Why or why not?

This exercise should take about 15 minutes.

Attention Management in Your Workshop

Carpentries lessons include small tasks arranged incrementally which are intended to be completed together, through participatory live coding (a technique we will discuss in more detail later in this training).

The choices you make as an Instructor may add to or subtract from your learners’ cognitive load. Supporting memory consolidation can reduce load later on in the workshop, as it reduces the effort of recalling forgotten material. You can also minimise cognitive load by choosing formative assessments that are narrowly focused and by considering potential distractions in what you display during instruction.

Using Formative Assessments for Memory Management

There are many different types of exercises that can focus attention narrowly and help to avoid cognitive overload. Carefully targeted multiple choice questions can play this role. A few more that you may wish to consider are:

- Faded examples: worked examples with targeted details “faded” out – essentially fill-in-the-blank programming blocks

- Parson’s Problems: out-of-order code selection & sorting challenges

- Labelling diagrams or flow charts (may also be organised as a fill-in-the-blank)

Beware of assessments that are too open-ended, as these are very likely to induce cognitive overload in novice learners! You may have experienced some overload already when you were asked to create a concept map; this is why we do not recommend these as an activity for novice learners. Questions that ask learners to both remember and synthesise or reason with new information are also risky. If you try out a question and get a room filled with silence, you may need an icebreaker, you may need to re-teach… or you may only need a more narrowly focused question.

What to Display

The Carpentries provides nicely formatted curricula for teaching. However, you may have noticed that you have not seen much, or perhaps any of the Instructor Training curriculum during your time as a learner in this training. In most situations we do not recommend displaying Carpentries curriculum materials to your learners while you teach.

The visual environment in a workshop should be focused on exactly what you are teaching and should mirror, as closely as possible, exactly what you say. This is because keeping track of distracting and contradictory sensory information adds to cognitive load. The split-attention effect describes the cognitive effort involved with trying to assemble information from different modalities. Learning is most effective when visual displays, text, and auditory information presented together are the same, with minimal distractions.

For Carpentries workshops, this is why we ask Instructors to speak commands as they type them on the screen while engaging learners in participatory live coding.

One thing you may wish to consider adding to your (otherwise minimalist) visual environment, however, is a running glossary of commands and other key terms. This can be maintained by a helper on a white board or an easel pad and will help learners readily access items that may have already been dropped from short-term memory by the time they need them. In an online workshop, display of a glossary is impractical because of severe limitations on screen space; however, a glossary can still be maintained in a collaborative document for reference as needed.

Summary

The process of learning is constrained by the limits of short-term memory. In order to move new information into long-term memory, it must be actively applied, but activities that make excessive demands on short-term memory are likely to induce cognitive overload and can easily harm learner motivation. Instructional tools that expand short-term memory by increasing connectivity (chunking) among new concepts can improve outcomes for subsequent memory-intensive exercises. Formative assessments, when performed frequently, help learners by prompting them to apply new content before it has been overwritten. Faded examples or other types of guided practice both minimise demands on short-term memory and offer context that helps improve connectivity for future work, in which the “scaffolding” of contextual support can be gradually removed. Anything you can do to a) recognise and b) support learners in working with the limitations of short-term memory will improve the effectiveness of your teaching.

- Most adults can store only a few items in short-term memory for a few seconds before they lose them again.

- Things seen together are remembered (or mis-remembered) in chunks.

- Cognitive load should be managed through guided practice to facilitate learning and prevent overload.

- Formative assessments can help to consolidate learning in long-term memory.

Content from Building Skill With Feedback

Last updated on 2025-08-15 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I get feedback from learners?

- How can I use this feedback to improve my teaching?

Objectives

- Describe three feedback mechanisms used in Carpentries workshops.

- Give feedback to your instructors.

We use formative assessment of learners during workshops to help track learners’ progress and adjust our approach to teaching the content as needed. But formative assessment is not just for learners. As we will discuss in more detail later, teaching is also a skill that is improved through regular practice and feedback. We gather feedback from our learners at multiple points in the workshop and in different forms.

Surveys

Carpentries learners fill out a survey before attending and immediately after a workshop. These surveys include questions to help instructors get an idea of their attendees’ prior experience and backgrounds before the workshop starts. Using this information, instructors can start to plan how they will approach the materials and what level of exercises are likely to be appropriate for their learners.

You can preview the surveys your learners will take at the links below:

If you’d like have an overview of the questions asked in the surveys without having to go through all the questions, you can preview them in a text-format below:

When The Carpentries Workshops and Instruction Team sets up the surveys for your workshop, they will also send you a link to a dashboard with the results! Take care not to share this link with your learners.

- The Carpentries maintains a dashboard displaying data from past workshop surveys, so you can have an idea of what to expect for your workshop.

Survey links

The survey links above are only for you to preview the survey as part of Instructor Training. When you are teaching a workshop, make sure to share the links that get generated on your workshop website. Doing so will ensure that you will receive all the survey results from your workshop participants.

Timing Matters

We have found that learners are much more likely to fill out the post-workshop survey while they are still at the workshop than they are after they leave the venue. At the end of a multi-day workshop, your learners’ brains will be very tired. Rather than trying to fit in another 15 minutes worth of teaching, give your learners time to complete the post-workshop survey at the end of your workshop. You will be helping them (with an opportunity to reflect), yourself (you will get more useful feedback), and The Carpentries (we improve our programs based on feedback, and our funders take pride in the success of our workshops, too).

Minute Cards

Before each long break, for example lunch or between days, we have learners complete minute cards to share anonymous feedback. At an in-person workshop, paper sticky notes double as minute cards, with the two different colours used for positive and constructive feedback. At an online workshop, this may be done by making a copy of our Virtual Minute Card Template on Google Forms. Other tools can work as well, but we do recommend making sure that feedback is private and anonymous. A public-facing sticky note board will receive different (and less useful) feedback.

Whatever method you use, you may wish to customise the prompt to elicit different types of feedback at each break.

Example positive prompts:

- One thing you liked about this section of the workshop

- The most important thing you learned today

- A new skill, command, or technique you are most excited about using

Example constructive prompts:

- One thing you did not like or would change about this section of the workshop

- One thing that is confusing / you would like clarification on.

- One question you have

During long breaks, instructors read through the minute cards and look for patterns. At the start of each half day, the Instructors take a few minutes to address commonly raised issues with the whole class. The non-teaching Instructor can also type answers to the questions in the Etherpad.

Be Explicit About Using Feedback

Learners are more likely to give useful feedback if they feel that their feedback is being taken seriously. Spending a few minutes talking about the feedback you got and being explicit about what changes you are making in light of that feedback will encourage learners to continue to give informative feedback throughout the workshop.

One-Up, One-Down

In addition to minute cards, we also ask learners to give us feedback at the end of each day using a technique called “one up, one down”. The instructor asks the learners to alternately give one positive and one negative point about the day, without repeating anything that has already been said. This requirement forces people to say things they otherwise might not: once all the “safe” feedback has been given, participants will start saying what they really think. The instructor writes down the feedback in the Etherpad or a text editor, but does not comment on the feedback while collecting it. The instructors then discuss this feedback and how they plan to act on it. Like with minute cards, be explicit about how you are responding to learner feedback.

Give Us Feedback

If in person Write one thing you learned so far in this training that you found useful on your blue sticky note, and one question you have about the material on the yellow. Do not put your name on the notes: this is meant to be anonymous feedback. Add your notes to the pile by the door as you leave for lunch.

If online Complete the virtual minute card form as provided by your trainers, not using the template and creating your own form, but completing the version your trainers provide

- Give your learners time to fill out the post-workshop survey at the end of your workshop.

- Take the time to respond to your learners’ feedback.

Content from End Part 1

Last updated on 2024-03-11 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 0 minutes

Take a break. If you can, move around and look at something away from your screen to give your eyes a rest.

Content from Motivation and Demotivation

Last updated on 2026-02-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 60 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why is motivation important?

- How can we create a motivating environment for learners?

Objectives

- Identify authentic tasks and explain why teaching them is important.

- Develop strategies to avoid demotivating learners.

- Distinguish praise based feedback on the type of mindset it promotes.

In an online training, ensure that captions are turned on, that one trainer claims host, and that the host adds other trainers as co-hosts. The host key is in the email to trainers from the core team prior to the training.

Motivation Matters

Teaching and learning are not the same process. As we have seen, an instructor can make choices that facilitate the cognitive processes necessary for learning to occur. But any technique can fall flat when learners are not motivated. Worse, demotivation is contagious! Teaching or sharing a classroom with demotivated learners is not fun or rewarding. It can be tempting, especially for teachers facing burnout after strenuous and ineffectual effort, to blame learners for spoiling the classroom experience.

It is true that learner motivation is influenced by many factors well beyond the control of an instructor, including individual background and systemic forces. However, there are many things you can do to cultivate motivation in your classroom, and perhaps most importantly, to avoid doing harm to the precious drive your learners bring to the classroom on day one. In Carpentries workshops, most learners come eager to learn! You have the power to influence how they feel when they depart.

No two-day workshop can truly bring a total novice to the level of a competent practitioner. Carpentries workshops function in a context of self training, in which workshops offer vital tools and a map for learners to proceed on their own. Our workshops lower the barrier to entry and help learners to get off on the right foot. In this context, cultivating motivation to continue learning, and to carefully pursue best-practices in doing so, is arguably the most important outcome we can achieve.

This section discusses several ways that learners can be motivated (or demotivated!) by instructional content and approaches, and provides practice opportunities for you to become confident in motivating your learners.

How Can Content Influence Motivation?

People learn best when they care about a topic and believe they can master it with a reasonable investment of time and effort. Many scientists might appreciate the value of programming but believe that developing useful skills will take more time than they have available. This presents a problem because believing that something will be too hard to learn often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

One way to combat this problem is to begin a lesson with something that is quick to learn and immediately useful. It is particularly important that learners see it as useful in their daily work. This not only motivates them, it also helps build their confidence in us, so that if it takes longer to get to something they find useful in a later topic, they will persist with the lesson.

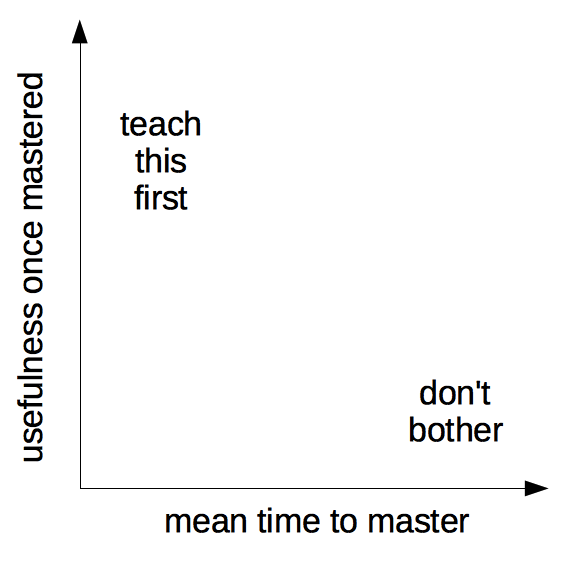

Imagine a graph whose axes are labelled “mean time to master” and “usefulness once mastered”. Tasks that are quick to master and immediately useful should ideally be taught first; things in the opposite corner that are time-consuming to learn and have little near-term application should be avoided in our workshops.

Another way to think about the graph shown above is authentic tasks – real tasks performed by someone doing their work. If you can identify authentic tasks from your own work that could be useful to others, these examples will be highly motivating.

Actual Time

Any useful estimate of time must take into account how frequent failures are and how much time is lost to them. For example, editing a text file seems like a quick task, but most graphical editors save things to the user’s desktop or home directory. If a novice needs to run shell commands on the files they’ve edited, they often fail to navigate to the right directory without help. You will learn to anticipate these sorts of challenges as you chart your expert awareness gaps. As a result, your skill at estimating time to mastery will improve. If you are new to teaching, try to ask an experienced instructor for feedback before trying out a new exercise.

While we aim to begin workshops with motivating content, in practice this does not always occur. Workflow-based content like that taught in Data Carpentry workshops may start at the beginning of the workflow, for example. Even when a ‘motivating example’ is built in to the start of a workshop, technical problems like software installation can turn those precious first minutes into an experience of frustration and impatience. That is ok! What is important is to be mindful of times when your content is not motivating, and to strategise ways to re-engage learners (and yourself) using some of the other techniques in this section.

How Can You Affect Motivation?