How to Write a Lesson

Last updated on 2023-07-10 | Edit this page

Estimated time 70 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why do we write explanatory content last?

- How can I avoid demotivating learners?

- How can I prioritise what to keep and what to cut when a lesson is too long?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Estimate the time required to teach a lesson.

- Summarise the content of a lesson as a set of questions and key points.

- Connect the examples and exercises in a lesson with its learning objectives.

Writing Explanatory Text

Explanatory text helps connect your examples and exercises together into a cohesive lesson. If your examples and exercises are train stations and scenic views, the explanatory text is the train tracks that connect them. Often times the examples and exercises may seem like a good draft for you to teach. However, the explanatory text makes it possible for other instructors and self-directed learners to follow along by providing all the relevant information directly in the lesson. It can also help you remember your goals and stay on track teaching.

How much text to include is often a question of personal style while balancing the needs of potential users, both other instructors and learners. You want to find the balance between providing enough information for learners to meet the learning objectives without increasing cognitive load with extraneous information. In this section we will discuss factors to consider when you are writing explanatory text.

There are trade-offs to consider when preparing a site for use as an instructional guide vs use as a self-directed learning resource. Typically, self-directed learning resources are more verbose where instructional guides are aimed at an audience that can fill in the gaps on their own. However, very sparse text is less likely to be re-usable by other instructors as instructors may have different skill levels with the lesson content or differing mental models. In general, it is not a good idea to assume others, learners or instructors, will know what you were thinking when you wrote the content so, if in doubt, be explicit.

Using Callouts

Often lessons have more content than can be reasonably taught in the amount of time allotted. This is especially true for collaboratively developed lessons as each contributor/instructor may have additional items they’d like to see included, leading to “scope creep”.

To address this issue, in many Carpentries lessons, callout boxes are used for asides and short tangents, e.g. points that might be relevant to some audiences but are not essential to the flow of the lesson. These callouts should still be kept to a minimum as they can be disruptive to instructors and readers.

Less is More

Trying to fit too much content into a lesson is counter-productive. It is better to cover less and provide a smaller but stable foundation for learners to build upon.

You should also consider a realistic workshop length for teaching your lesson. It is difficult to keep learners attentive for many hours over many days. Most Carpentries workshops are two work days of lesson material as it is difficult for learners to attend 4 full days of a workshop. Although, there are some in the community who will run workshops that are three days to cover additional material.

As you consider the length of your lesson discuss with your collaborators and ask yourself:

- What is essential to include?

- What can be left out if needed?

- Are there checkpoints where the lesson could end if needed?

- Can important concepts be moved up earlier to ensure they are covered?

In the end, the only way to know for sure is to teach the lesson, measuring how long it takes to teach. Borrowing from television, the Carpentries community calls these early workshops, pilot workshops. As you run pilot workshops, you can note the length of time spent in each episode. You might find the template for notes on pilot workshops helpful as it includes a table for episode and exercise timings. Instructors commonly report running short on time in workshops. Thus, it is better to assume that you are under-estimating rather than over-estimating the length. It is better to have additional time for discussion, review, and wrap-up than to rush through material to fit it into the remaining time.

If, after piloting your new lesson, you find that you did not have time to cover all the content, approach cutting down the lesson by identifying which learning objectives to remove. Then take out the objective(s) and the corresponding assessment(s) and explanatory content. You may consider making a concept map to help identify which objectives depend on one another.

Alternatively, if you decide to keep certain objectives in the lesson, you can add suggestions on which objectives can be skipped to the Instructor Notes for the lesson.

Callout

The Instructor Notes for the whole lesson should be added to the

instructors/instructor-notes.md file. This page is

displayed in the header menu when in “Instructor View”. You can also add

notes in

a specific episode of the lesson using fenced divs. Instructors can

see the notes within the lesson and the instructor notes tab by changing

the view in the upper right-hand corner of the lesson to “Instructor

View”.

Try out the instructor view by opening this episode seeing the in-line instructor note below.

We will discuss the content of Instructor Notes in more detail later on in section “Preparing to Teach”.

This is the hidden note! Thanks for developing new incubator lessons for others to use!

As you add notes and think about what to cut, remember, reducing the number of lesson objectives can help with managing learner (and instructor) cognitive load.

Testimonial

“the five ways to handle an extraneous overload situation are to:

- eliminate extraneous material (coherence principle),

- insert signals emphasizing the essential material (signaling principle),

- eliminate redundant printed text (redundancy principle),

- place printed text next to corresponding parts of graphics (spatial contiguity principle), and

- eliminate the need to hold essential material in working memory for long periods of time (temporal contiguity principle).”

Other Important Considerations for Lesson Text

When writing your lesson text you also want to avoid unintentionally demotivating your learners. Make time to review your text for:

- dismissive language - e.g. ‘simply’, ‘just’

- use of stereotypes (check learner profiles for stereotypes too)

- expert awareness gaps, i.e. places where you may be assuming the learners know more than they actually do

- fluid representations, i.e. using different terms with the same meaning interchangeably

- unexplained or unnecessary jargon/terminology (as your learners may come from different backgrounds, may be novices, not native English speakers, and a term in one domain/topic may mean something else entirely in another)

- unexplained assumptions

- sudden jumps in difficulty/complexity

You should also review your text thinking about accessibility. This includes:

- Avoiding regional/cultural references and idioms that will not translate across borders/cultures

- Avoiding contractions i.e. don’t, can’t, won’t etc.

- Checking that all figures/images have well written alternative text, including writing altnerative text for data visualizations. An alternative text contains an invisible description of an image which is read aloud to blind users by screen readers providing alternative text-based format for images. See the Workbench documentation for directions on how to add alternative text and captions to images in a lesson

- Checking the header hierarchy - no h1 headers in the lesson body, no skipped levels

- Using descriptive link text - no “click here” or “this page”, etc.

- Checking the text and foreground contrast for images

Optional Exercise: Alternative Text for Images (5 minutes)

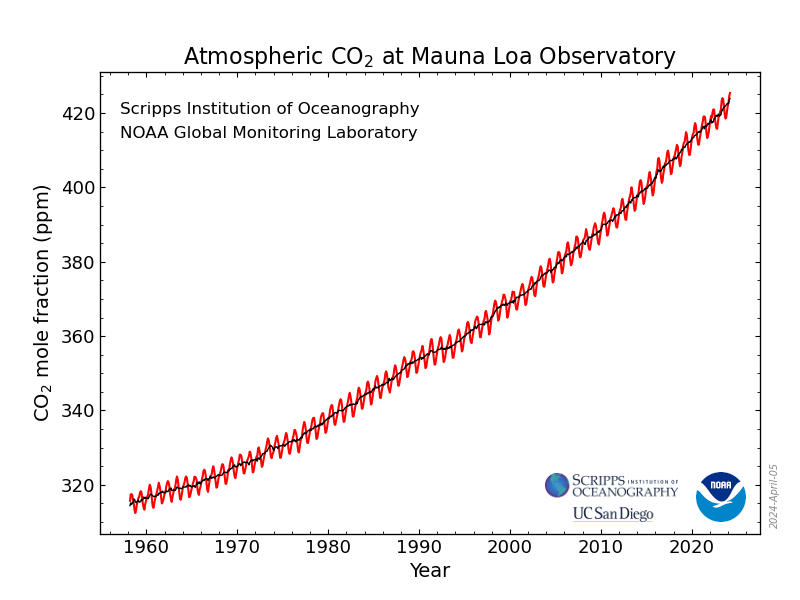

Which of the following is a good alt-text option for the image below?

- Graph of data

- Graph with increasing lines

- Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory from 1958 to present

- Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, United States, from 1959 to present including values from each year. Red line shows variation in each year and black line is average for each year. 1959 = 315.90 ppm, 1960 = 316.91, 1961 = 317.64 …

Data/Image provided by NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, Boulder, Colorado, USA

The third option, “Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory from 1958 to present”, is the best option. It describes the type of plot, what is measured, and the trend.

The first two options are too vague. They mention a graph but don’t give enough info to know what the graph is actually showing.

The last option is overly descriptive and starts to list the data itself. It is better to include a shorter, but informative, description and a link to the data instead.

May want to point out that the answers in the current version of this exercise do not have diagnostic power.

Other Text to Complete an Episode

When writing a lesson, you should also consider adding key terms to the lesson glossary for the lesson. Following the instructions on how to create a glossary in the Workbench documentation will help you to create this section of the lesson.

Many of these terms may also be useful for other lessons and can be added to Glosario, a multilingual glossary for computing and data science terms.

In addition to objectives, a completed episode also requires fenced divs for the questions the episode answers and the keypoints a lesson covers. The questions box helps learners understand what to expect from a lesson as they might not yet understand the learning objectives. The keypoints box wraps up the lesson by providing answers to each of the questions. Keypoints also help self-directed learners review what they learned, remind instructors to recap what was covered in an episode, and help you ensure you answered all the questions you intended for an episode.

Exercise: Completing episode metadata (10 minutes)

Add key points and questions to your episode.

To check the formatting requirements, see the Introduction Episode example in your lesson or the Workbench Documentation

Polishing a lesson

Lessons do not need to be perfected prior to teaching them the first time. In fact, keeping things relatively basic leaves you some flexibility while you run through the first few iterations of teaching the lesson, collecting feedback, and using that to guide improvements.

However, once you find that the lesson is beginning to reach something like a stable state, you may find the checklist for lesson reviewers in The Carpentries Lab useful as a guide for polishing the design and content. The checklist describes criteria for a lesson to meet a high standard in terms of its accessibility, design, content, and supporting information.

Reflection Exercise (20 minutes)

We have reached the end of the time you have to work on the episodes of your lesson in this training. This exercise provides you with a chance to look back over everything you have sketched out for your episode and the lesson as a whole and consider what still needs to be done before it can be taught.

You can use this time however you judge will be most beneficial to your preparations for teaching your episode in a trial run.

If you are not sure how to start, consider mapping out the relationships between the objectives of your episode and the examples and exercises via which they will be taught and assessed. For example,

The read CSV and inspect demo supports Objective 2 (load a simple CSV data set with Pandas) and will be delivered using participatory live coding. The objective will be assessed with an exercise that requires learners to apply the read_csv function to another file and count the rows in the resulting DataFrame object.

Does any of your planned content not support any learning objectives?

Is there at least one piece of content planned for each learning objective?

Is there a formative assessment planned for each learning objective?

What do you still need to add/work on?

What can you remove/consider removing?

How will the narrative and example data you have chosen for your lesson support teaching and assessment?

What diagram or other visual aids could you add to supplement your text?

Keypoints

- The objectives and assessments provide a good outline for an episode and then the text fills in the gaps to support anyone learning or teaching from the lesson.

- It is important to review your lesson for demotivating language, cognitive load, and accessibility.

- To reduce cognitive load and ensure there is enough time for for the materials, consider which lesson objectives are not needed and remove related content and assessments.