Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is covered in this training?

- Who are the trainers?

- Who is participating?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Explain how trainers and participants will interact throughout the workshop.

- Summarise the main skills that will be taught in this workshop.

You might like to make a copy of the template CodiMD notetaking page and share your link with trainees so that you can take notes together during the training.

Note: some of the content in this course is reproduced or adapted from The Carpentries Instructor Training curriculum.

Pronouns and Names

Using correct names and pronouns (e.g. “she/her”) is important to setting a tone of respect. Learning these is hard to do quickly, so we recommend displaying it prominently during the workshop.

In an online workshop, give everyone a moment to update their display name to reflect how they would like to be addressed.

At an in-person event, we recommend supplying name tags and markers, or using plain paper to create table-displayed name placards.

Note that pronouns are personal and some participants might prefer not to share them. Do not force people to share their pronouns.

Before The Training Begins

Getting to Know Each Other

If the Trainer has chosen an icebreaker question, participate by writing your answers in the shared document for the workshop.

Code of Conduct

To make clear what is expected, everyone participating in The Carpentries activities is required to abide by our Code of Conduct. Any form of behaviour to exclude, intimidate, or cause discomfort is a violation of the Code of Conduct. In order to foster a positive and professional learning environment we encourage you to:

- Use welcoming and inclusive language

- Be respectful of different viewpoints and experiences

- Gracefully accept constructive criticism

- Focus on what is best for the community

- Show courtesy and respect towards other community members

If you believe someone is violating the Code of Conduct, we ask that you report it to The Carpentries Code of Conduct Committee by completing this form.

Today’s Trainers

To begin class, each Trainer should give a brief introduction of themselves.

(For some guidelines on introducing yourself, see the Workshop Introductions section of the Instructor Training curriculum).

Now, we would like to get to know all of you.

Our First Exercise (10 minutes)

Think of an example of a great a lesson that you have followed (were taught in a class, read through online, read in a book).

- What did you find was so good about it?

- Why did it make such an impression on you?

Try to differentiate between what was good about the performance of the teacher/trainer and what was good about the content of the lesson itself. Take a few minutes to write down some notes about your answer, then introduce yourself to the other participants and tell them about it.

Collaborative Lesson Development Training Overview

The main objective of this training is to teach you the skills you need to design and develop an effective lesson, in collaboration with other members of the community.

During the training, we will introduce the steps you can take to design and develop a lesson to meet the needs of your target audience, and give you time to begin implementing those steps during the workshop itself. By the end of the training, you can expect to have defined an outline for your whole lesson, and begun filling in a detailed plan for some of its individual sections. The content you create in the training will exist as an open source lesson website similar to the one this training is based on. You should also know how you can continue building on the lesson and have some plans for how you will collaborate on the project after the training ends.

We will focus on three main areas:

Designing a Lesson

Much of the training will discuss a process to incorporate good practices in lesson design. We will explore how defining the specific skills you wish to teach early on in the development process provides a foundation from which you can build a stronger, more impactful lesson.

Building a Lesson Website

Throughout the training, while you design and begin developing the content of your lessons, we will teach you how to incorporate this into an organised and accessible website using our lesson infrastructure.

Collaborating Effectively

We believe that lessons are much more likely to succeed, and to remain useful in the long term, if they are developed collaboratively. We will spend a little time talking about how you can work together effectively during this training. To further develop your collaboration skills after the training, we recommend that you join one of the regular GitHub Skill-up sessions hosted by The Carpentries. Participation in those skill-ups is optional but included in your registration for this training.

Learning How to Teach a Lesson

This training will focus on the content – how to prepare a good lesson. More about the performance – how to deliver a lesson most effectively – is covered in The Carpentries Instructor Training.

- This training aims to teach you a process for designing a lesson and the skills to develop it as an open source website, in collaboration with others.

Content from Lesson Design

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the recommended steps to take when developing a new lesson?

- What lesson do you want to develop during and after this workshop?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Explain the lesson design process we will be adopting for this course.

- Summarise the lessons that participants will be working on.

A Lesson Design Process

In order to design an effective lesson, we need a structured approach with the learner in mind and clearly identified goals. Throughout this training we will use a modified version of a process for curriculum design commonly referred to as backward design, described by Gill Nicholls1. Following Nicholls’ paradigm, we begin by defining exactly what you want your learners to be able to do after they have completed the lesson/training/course, with the subsequent stages involving the design and evaluation of content that will directly help learners meet those stated outcomes. By defining at the beginning of the process what you want the outcomes to be at the end, you ensure that your efforts remain focused on those goals as you work.

This training promotes an iterative backward design process where, after identifying the target audience of our lesson, we

- Define desired learning outcomes.

- Design assessments to determine progress towards desired outcomes.

- Write content to lead learners from one of these assessments to the next.

- Assess learner progress towards outcomes during teaching.

- (After the break) evaluate how closely the outcomes meet the objectives.

The process throughout this training

Note the cyclical nature of the process described above. By the time you have completed your certification as a Carpentries Lesson Developer, you will have completed one iteration through this cycle:

- Define desired learning outcomes.

- You will define learning objectives for your lesson as a whole and for individual sections.

- Design assessments to determine progress towards desired outcomes.

- You will learn about different types of assessment and how they can give you information about your learners’ progress towards the defined objectives.

- You will design and implement exercises that are appropriate to your target audience and the skills you want to teach them.

- Write content to lead learners from one of these assessments to the

next.

- You will choose examples and a narrative that can help learners gain insight into the topic of your lesson.

- You will begin to write content that is accessible, relevant, and appropriate for your target audience.

- Assess learner progress towards outcomes during teaching.*

- You will deliver part of your new lesson and gather information about how effectively it teaches learners what they need to know.

- Evaluate how closely the outcomes meet the objectives.*

- You will revisit your lesson design and content and make plans to update it, based on your own reflections and the feedback you gathered from learners.

Teaching the new lesson content is an essential intermediate step in the process and the steps marked with an asterisk (*) will be completed after the training, as part of the checkout process for certification (more on which later). The importance of gathering feedback and reflecting on teaching experience will be a common refrain throughout this training.

Your Lessons

This training will provide many opportunities for discussion of your lessons. Providing some context now for the lessons that you will be creating will help the Trainers and other participants get involved in those discussions and give you feedback as you follow the process.

Discussion (10 minutes)

Share your answers to the following questions in the shared notes, then discuss them with the Trainers, your collaborators, and the other participants.

- What is the topic of the lesson that you plan to develop based on this training?

- Have you created training material on this topic before?

- What is motivating you to create this lesson?

Trainees should have received the questions above in advance and arrived at the training with notes prepared. Where multiple trainees are working on the same lesson project, ask for a volunteer or call on someone to represent their team, leaving space afterwards for their team-mates to speak up if their answers differ.

The main objectives of this discussion are:

- to ensure that the members of each collaborative team share a common vision for the lesson they want to create

- to help Trainers and collaborators understand each trainee’s motivation for attending the training and building their lesson

Iterative Development

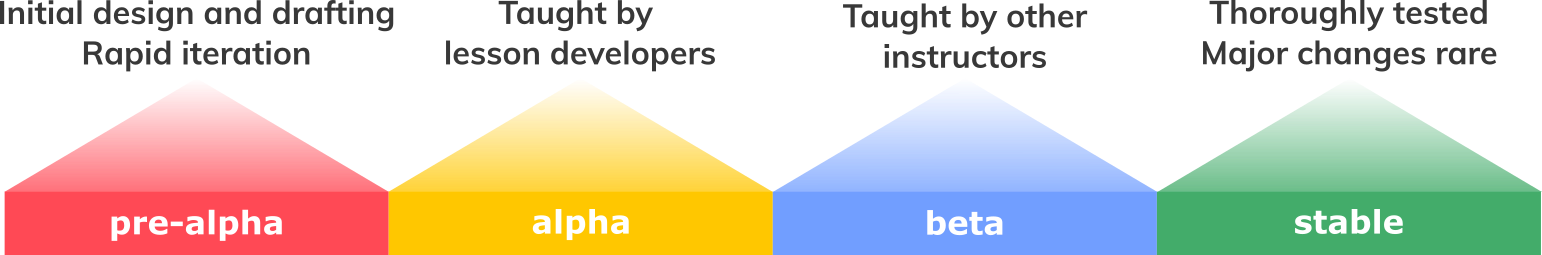

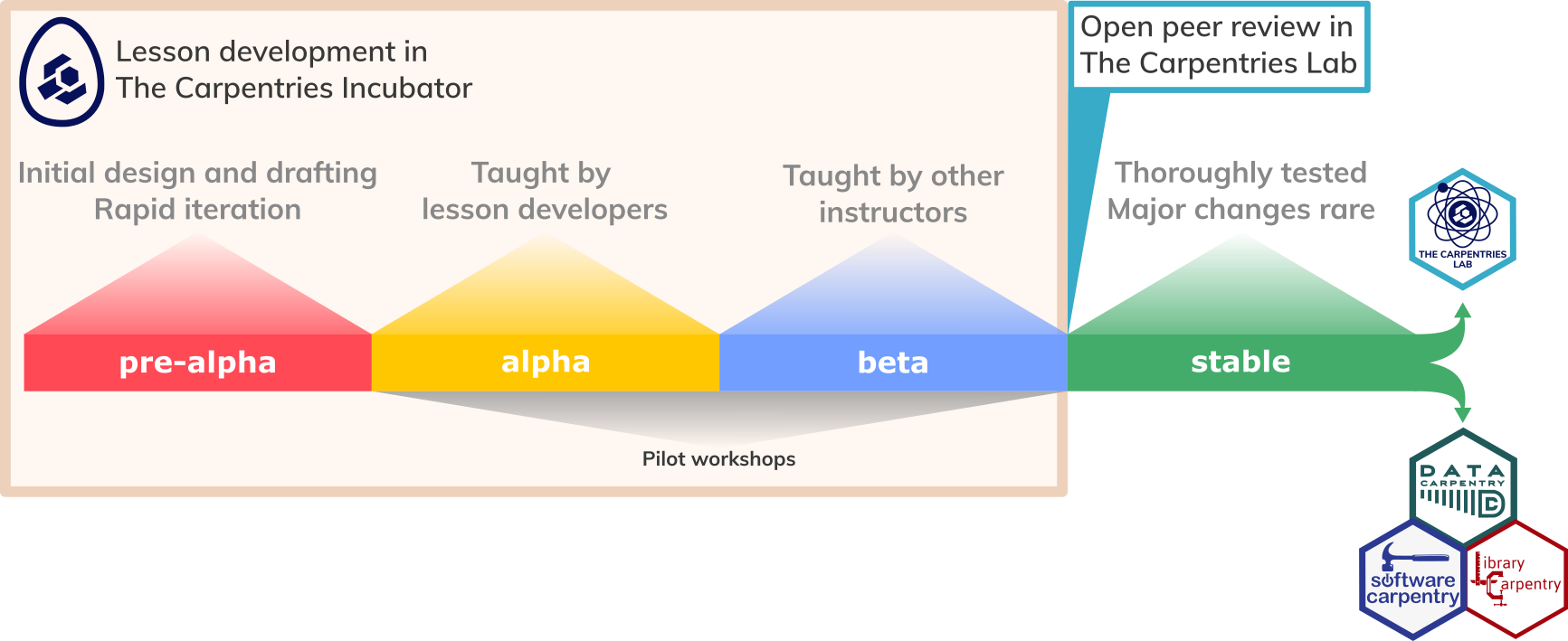

The Carpentries community develops open source lessons, which can always be updated and may never be finished. A lesson can undergo many iterations before it reaches a relatively stable state. To reflect this, we encourage lesson developers to indicate the status of their lesson by labelling its progress through a lesson life cycle:

Each life cycle stage indicates the level of maturity of a lesson:

- pre-alpha: a first draft of the lesson is still being constructed.

- alpha: the lesson has been/is being taught by the original authors, but has not been fully tested.

- beta: the lesson is ready to be taught by instructors who have not been significantly involved in its development to this point.

- stable: the lesson has been extensively tested by the authors and others. It can be considered broadly complete and unlikely to undergo any drastic changes without warning.

Although your lessons will probably remain in pre-alpha throughout this training, some of the content will be equally valuable at later stages and we will also point you towards resources to help with testing the lesson and gathering feedback.

The Carpentries Community Handbook provides more information about the lesson life cycle.

Lesson Design Notes Template

At this point, the Trainers will share a template document for Lesson Design Notes with trainees. Trainees should make a copy of this document and fill in their lesson title. They will populate other parts of the document with the notes and information they produce throughout the training.

- We will learn to develop lessons based on the (slightly adapted) Nicholls’ backward lesson design process.

- There can be many reasons to create a new lesson.

- This training will give you a process to follow to ensure your lesson is effective.

Content from Identifying Your Target Audience

Last updated on 2025-10-17 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why is it so important to think about the target audience early in the process?

- How can you ensure that your lesson reaches the right audience?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Describe the importance of aligning lesson design with the intended audience.

- Compose a list of prior knowledge required to follow a lesson.

Target Audience

Given the limited time in a short-format training, it is vital to define the scope of the lesson, i.e. what people need to know before and what they will know after the lesson. Thinking carefully about the target audience will help you with this and with defining desired learning outcomes (the first step of the lesson design). Prominently displaying a description of the target audience will also help attract people with the right motivation and relevant prior knowledge to attend your workshops.

Expertise

One of the most important things we can identify about our target audience is the level of expertise they will already have in relation to the skills taught in your lesson. In The Carpentries Instructor Training curriculum, we describe three different stages of skill acquisition: novice, competent practitioner, and expert and how these stages directly correlate to the complexity of mental models these different groups have about a domain/topic.

Briefly, the novice is someone who does not know what they do not know, i.e., they do not yet know what the key ideas in the domain are or how they relate, the competent practitioner has enough understanding of the domain/topic for everyday purposes, and the expert is someone who can easily handle situations that are out of the ordinary and can immediately use their prior knowledge or skills when presented with a new problem in the domain.

When designing a new lesson, it is important to think about the level of expertise that you expect learners to arrive with for two reasons:

- It helps to predict what prior knowledge and mental

model learners will have of the lesson domain when they arrive. This

can enable you to make progress quickly by

- working to help learners recall (activate) that prior knowledge1,

- building on the conceptual understanding they already have2 and,

- perhaps most importantly, giving you some idea of what misconceptions they might arrive with. It is vital that misconceptions are identified and corrected early on, before learners try to incorporate new knowledge into a broken mental model. (More on this in Designing Exercises.)

- People at different stages of this process need to be taught differently. For example, novices will learn more from lessons that include worked examples and are more tutorial-like i.e. focused on a specific task, with step-by-step explanations of the process, but without a lot of extra information that is not directly relevant. However, the same approach may actually hinder learning for competent practitioners who may be distracted by a step-by-step explanation of something they already have the prior knowledge of3. For learners at this level of expertise, lessons which include activities offering learners the freedom to explore options and develop their own solutions, are likely to be more effective.

Motivation

Furthermore, your lesson will be more effective if it aligns with the motivations of the target audience. Understanding the wants and needs of your target audience, what they know already and what kinds of problems they want to solve, will help you design a lesson that learners can see the value in. It will give them the impression that taking the lesson will be worthwhile (called positive expectancies in the literature).

We will look more at strategies to establish value and build positive expectancies in the next episode.

Be Specific

It can be tempting to identify a target audience only in vague terms, for example by writing that a lesson is aimed at “PhD students” or “early career researchers”. However, taking the time to focus on real people, or imagined personae, who represent your target audience will help you take time to consider the various aspects that can influence how much someone will learn from your lesson. It will also help you notice when the assumptions you are making about your target audience are unreasonable.

Most of all, it will help you stay connected to the fact that you are not your learners: they will arrive at the lesson with different priorities, interests, and challenges than your own.

Exercise: thinking about target audience (15 minutes total for both parts)

Part 1 (all, 5 minutes): think about a member of the target audience for your lesson, and answer the following questions in the context of your lesson topic:

- What is their background?

- What do they already know how to do?

- What do they want to do with the skills they will learn from your lesson?

- What problem will your lesson help them solve?

Share your answers with your collaborators. How do they compare? If you have identified different audiences, are they compatible? Or would your time be better spent focussing on one particular audience for this lesson?

Take notes on your discussion in your Lesson Design Notes document. It can be particularly helpful to note down any decisions made e.g. potential target audiences that were explicitly discounted, and your reasons for doing so.

Take notes about your choice of target audience in your Lesson Design Notes document. It can be particularly helpful to note down any decisions made e.g. potential target audiences that were explicitly discounted, and your reasons for doing so.

Then write 1-2 diagnostic questions, for use before the lesson is taught, to help you assess whether a respondent falls within the intended audience for your lesson.

There is more to consider about your target audience than we could capture with only the questions listed above. In your own time, you should think more about the other considerations you might need to make when writing a lesson for your audience.

For example, what vocabulary do they use? The terms you are teaching in your lesson might have a different meaning in your learners’ domain of expertise, and it can be helpful to prepare for and try to avoid confusion arising from this clash. Furthermore, might their primary language differ from yours? If so, how might this change the way you write the lesson?

Defining Prerequisite Knowledge

A very common challenge encountered in workshops is heterogeneity of expertise among the audience. When learners arrive at a workshop with a wide range of previous experience with the topic, it is difficult for the instructors to keep everyone engaged. Those who arrive with too little relevant knowledge and experience can struggle to follow the lesson content at the pace you expect, while those who arrive with too much are likely to become bored and despondent as their expectation of learning new skills is not met.

One way to try to guard against this is to publish the description of your target audience when you advertise a workshop teaching your lesson, alongside a list summarising the skills and conceptual knowledge you expect learners to arrive with. Another is to use the information you have about your target audience to ask questions of potential learners when they apply/register to join the workshop (like the diagnostic questionnaire you may have prepared in the exercise above), and use the answers they give to filter out those who fall outside your intended audience.

While valuable, this kind of pre-assessment should be approached with caution: people are often bad at self-assessment i.e. estimating our own ability to perform a task4. We can try to mitigate for this when designing the questions for a pre-workshop survey, leaving little room for inaccurate self-assessment to confound the results. But experience suggests it is very difficult to ensure that every learner in a workshop falls within the intended audience of a lesson.

Exercise: defining prerequisite knowledge (5 minutes)

Write a list of the skills/knowledge your learners will be required to have before they can follow your lesson.

If you are struggling with this exercise because your lesson audience is novices, think about skills like touch typing, using a web browser, or interacting with a command line or graphical interface. These are skills commonly overlooked by experts and competent practitioners.

- We recommend an iterative lesson design process that begins with identifying the target audience, before defining learning outcomes, then creating assessments, writing explanatory content, and evaluating the lesson in a workshop.

- Thinking about the target audience early in the design process helps to ensure that your lesson is built around the needs and motivations of real people.

- Use the description of your target audience to help attract people with the appropriate interests and prior knowledge to your lesson.

See chapter 1, How Does Students’ Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?, of Ambrose et al. 2010.↩︎

See chapter 2, How Does the Way Students Organize Knowledge Affect Their Learning?, of Ambrose et al. 2010.↩︎

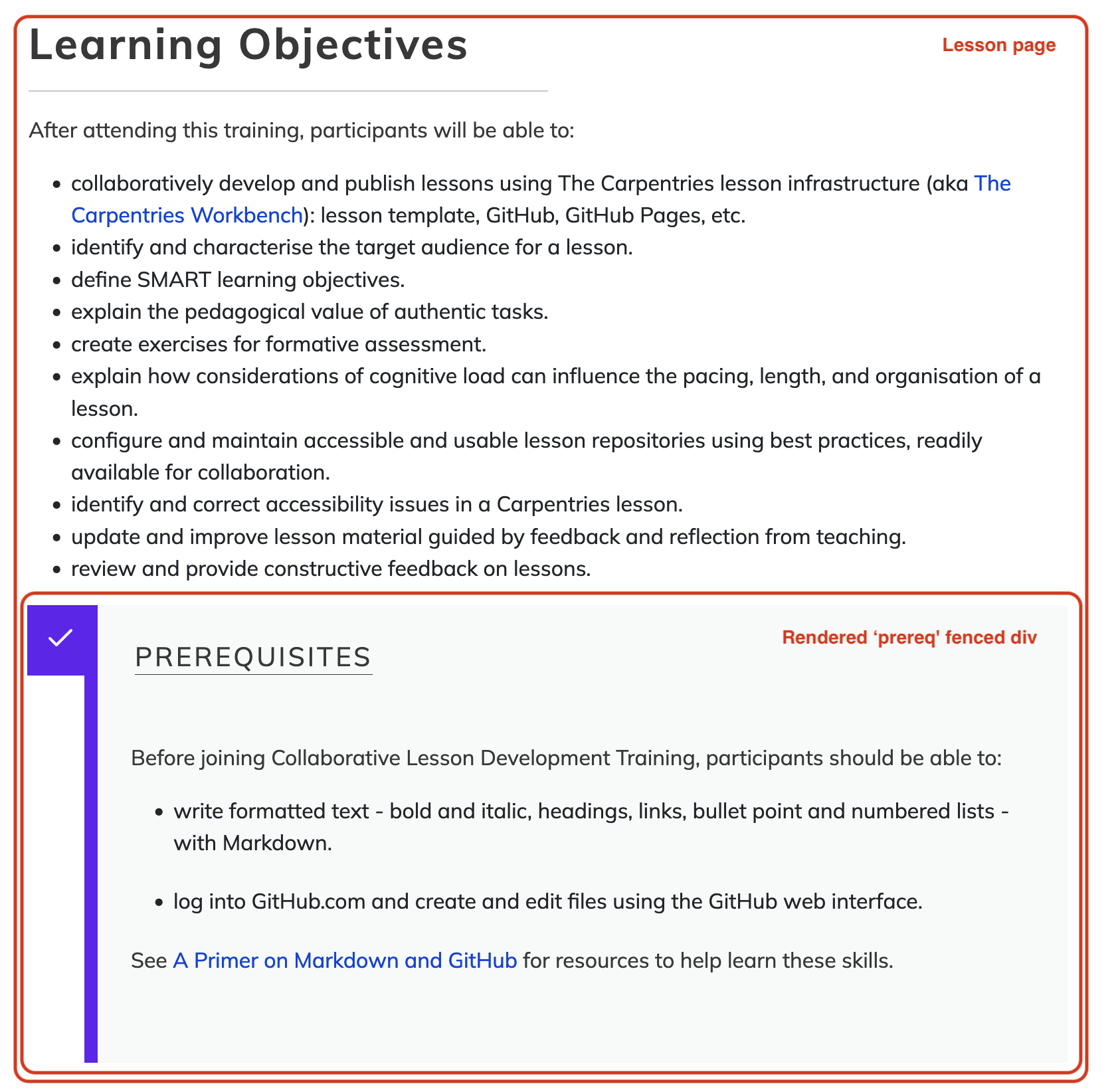

Content from Defining Lesson Objectives/Outcomes

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 80 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can describing the things you intend to teach aid the process of writing a lesson?

- How can you be specific and realistic about what you will teach in your lesson?

- What are some of the risks associated with unrealistic or undefined expectations of a lesson?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Explain the importance of defining specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound (SMART) objectives for a lesson.

- Evaluate a written lesson objective according to these criteria.

At this stage of the training, you should have a clear idea of who the target audience is for your lesson, and what knowledge, skills, and abilities you expect them to arrive with. Now it is time to consider the additional knowledge, skills, and abilities they will have by the time they leave: these are the learning outcomes of your lesson. It can feel strange to jump from one end of the process to the other like this, but clearly defining your goals early in the lesson development process is vital. As we will see in this episode, it helps you to determine the activities, examples, etc. that are appropriate for the lesson content, and provides a scope for what should and should not be included.

Why Focus on Skills?

To ensure your audience stays motivated, and your lesson feels relevant to them, we recommend that lessons focus on teaching skills rather than tools. Lessons should be centred around what you are empowering learners to do, what will be most beneficial to them, rather than a list of functions or commands you are teaching them to use. Placing the emphasis on skills over tools will help you prioritise key concepts and consider how your lesson can have the biggest impact on the way learners do their work.

Learning Objectives

The desired outcomes (the learning objectives) of a lesson should be new skills, i.e. things that the learner can do. For the vast majority of lessons, these will be cognitive skills: things learners can do with their minds. (Lessons intended to teach other kinds of skill, such as woodwork, playing a musical instrument, or making sushi, are probably better suited to a different platform than a static website.)

Cognitive skills cannot be equally easily acquired: before we can apply concepts and create something new, we must attain the ability to remember and distinguish between new concepts. Remembering and distinguishing are also abilities that are often faster to gain than applying or creating.

This is what Bloom’s Taxonomy (depicted in diagram below) tells us as well - it arranges cognitive skills (and educational objectives) into a hierarchy where cognitive skills on higher levels cannot be obtained before gaining those on lower levels. Even though Bloom’s Taxonomy has been disputed by some educational psychologists and has been revised since the original proposal - it still provides a useful framework to help us define learning objectives (as we will see shortly).

We must try to be realistic about how far along this scale we can move learners during a single workshop/lesson. This is one reason why the target audience is so important: if we can predict what learners will know when they arrive at the lesson, we can better define the outcomes we can expect when they leave.

Defining objectives for a lesson is essential because it allows us to focus the rest of our time on developing content that is necessary for learners to reach these goals. It will help us ensure we do not miss anything important or, conversely, include anything superfluous that could use up valuable time or distract instructors and learners.

What Does a Learning Objective Look Like?

The following highlights the most important elements of a learning objective:

Learning objectives should be read as if they were endings to the following sentence:

“At the end of this session, learners should be able to …”

Each objective should start with a verb and describe one (and only one) skill the learner will obtain.

For objectives to be as helpful as possible, they need to be written in a way that will allow us to directly observe whether or not a learner has attained the skills we want them to. This means that the skills described by our objectives should be measurable: as a general rule, action verbs such as “explain,” “choose,” or “predict,” are more helpful than passive verbs such as “know,” “understand,” or “appreciate”, which are hard to directly assess and are often open to interpretation.

Refer back to Bloom’s Taxonomy - this time focusing on the right-hand side of the diagram showing the measurable actions used to help us describe knowledge, skills and abilities. It serves as a very useful bank of action verbs for use in learning objectives. The Committee for Computing Education in Community Colleges has also created a version of Bloom’s Taxonomy customized for computing-related training with an extended list of action verbs.

We will see how helpful it can be to use action verbs in learning objectives when we begin talking about exercise design in the coming episodes.

Lesson-Level vs. Episode-Level Objectives

Objectives can be defined for a lesson as a whole - answering the question “what should learners be able to do at the end of a workshop teaching this lesson?”.

Objectives can also be defined for individual sections within it - answering the question “what should learners be able to do after following this particular part of the lesson?”.

This is probably a episode-level objective because it is very specific. A corresponding lesson-level objective might be “read data and libraries into the Python environment”. It is still fairly specific but a bit broader in scope and contains several episode-level objectives.

The lesson-level objective for the current section of this training is:

define SMART learning objectives.

This objective also covers a later episode as well.

The episode-level objectives for the current section of this training are:

- Explain the importance of defining specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound objectives (SMART) for a lesson.

- Evaluate a written lesson objective according to these criteria.

SMART Objectives

To assist you in defining and writing learning objectives for your lesson, it can be helpful to turn to another popular framework for defining goals and objectives: SMART. Originally proposed to aid managers in the definition of business goals, and updated and adapted since to several other domains including education (see How to Write Well-Defined Learning Objectives for example1), the SMART acronym requires goals to be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound.

In the context of a lesson, SMART objectives should be:

- Specific: they should clearly describe a particular skill or ability the learner should gain.

- Measurable: it should be possible to observe and ascertain when the learner has developed the skill described in the objective.

- Attainable: the learner should realistically be able to acquire the skill in the time available in a workshop or by following the text of the lesson.

- Relevant: they should be relevant to the overall topic or domain of the lesson as a whole.

- Time-bound: they should include some timeframe within which the goal will be reached. For learning objectives, this is built into the approach described above.

Note that, for any lesson that will be taught in a fixed amount of time, attainable and time-bound are overlapping: learning objectives for your lesson will answer the question “What will learners be able to do by the end of this lesson?” and the time available to teach the lesson, combined with the expected prior knowledge of your target audience, will determine how attainable they are.

You may find this template of a Markdown table useful to share with your trainees before they complete the next exercise.

MARKDOWN

| Objective | Action verb? | Specific | Measurable | Attainable |

|-----------|--------------|----------|------------|------------|

| 1 | | | | |

| 2 | | | | |

| 3 | | | | |Note: if you are using the template CodiMD for notes, you will find this template table for the exercise included there.

If you are using Etherpad for collaborative notes in your training, you can use the template table for Etherpad instead.

Exercise: evaluating learning objectives (15 minutes)

Look at the example learning objectives below. Fill in the table for each objective, checking off the cells if you think an objective meets the criteria or leaving it unchecked if not. You should assume each objective is for a lesson to be taught in a two-day workshop. Note down any observations you make as you move through the list. If you have time, try to imagine the titles of lessons that would have these objectives. This part of the exercise should take 10 minutes.

At the end of this lesson, learners will be able to:

- create formatted page content with Markdown.

- program with Rust.

- fully understand GitHub Actions.

| Objective | Action verb? | Specific | Measurable | Attainable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 |

In the last five minutes of the exercise, we will discuss as a group how each objective might be improved.

| Objective | Action verb? | Specific | Measurable | Attainable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ✅ | ❓ | ❓ | ✅ |

| 2 | ❓ | ❌ | ❌ | ❓ |

| 3 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❓ |

Objective 1 is the closest to what we ideally want in a lesson objective, but it illustrates how difficult it can be to make an objective truly specific. For example, a more specific and measurable version of this objective could be:

write links, headings and bold and italicised text with Markdown.

Lesson Scope

One of the major challenges of lesson design is choosing what to include in a lesson: what the main points will be, in what order they will be introduced, how much detail can be provided, and how much time can be spent on each point. Especially when writing lessons for short format training like a Carpentries workshop, difficult decisions often need to be made about what can and cannot be included. Trying to fit too much content into a lesson is counter-productive2, so it is good to avoid the temptation to cram in more content than you have time to cover properly.

Writing learning objectives is a good opportunity to begin thinking about lesson scope, and can provide assistance when you are faced with a difficult decision about what content to cut out.

For instance, consider the order in which new skills must be acquired. Before learners can begin to acquire “higher-level” cognitive skills to perform creative and analytical tasks, they must first acquire the foundational knowledge and conceptual understanding of the domain. Furthermore, these higher-level skills take longer to acquire so, unless you can expect your target audience to arrive at the lesson with the relevant foundational knowledge and understanding, it is probably unrealistic to aim to have learners completing creative tasks before its end.

As should become clear through activities in the upcoming episodes, lessons can be broadly considered as blocks of content associated with a particular learning objective. This can be helpful when making choices about content to remove, because the task can be considered in the context of taking out whole learning objectives.

Defining Your Learning Objectives

We have discussed the importance of defining objectives early in the lesson design process, and looked at some examples of objectives written for other lessons. Now it is time to begin defining objectives for your own lesson.

Here are some recommendations to help you get started:

- Aim for 3-4 lesson objectives for every 6 hours your lesson will take to teach. (For example, this curriculum is designed to be taught in ~18 hours and has ten learning objectives.)

- These objectives are for your lesson as a whole: try to define the “end point” knowledge and skills you want learners to acquire. You can think of these as the things you would test in a fictional “final exam” your learners would be able to tackle.

- Later you will write “episode-level” objectives that should define intermediate steps towards the high-level objectives you identify for your lesson here.

Exercise: defining objectives for your lesson (20 minutes)

Write learning objectives for your lesson into the relevant section of your Lesson Design Notes document - what do you want learners to be able to do at the end of the workshop? When writing these lesson-level objectives, try to follow the SMART framework: make them specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound.

Take notes about the your discussion in your Lesson Design Notes document. A record of the decisions you made and your reasons for choosing these objectives can be very helpful for you and others to understand the design and scope of the lesson later.

If you find yourself writing very specific episode level objectives, keep them in your notes and try to think of a slightly broader objective that may contain several very specific objectives. We will come back and work more on episode objectives next in the training.

The exercise below can be skipped if needed to make up some time. If the Trainer does choose skip the exercise, they should share the link to the Lesson Objective Advisor tool for trainees to try out in their own time.

Exercise: reviewing lesson objectives (15 minutes)

Swap objectives written in the previous exercise with a partner (you can also explain or show them what you wrote about your target audience, but this not essential) and review them with the following questions in mind:

- Are the objectives clear?

- Do they use “action” verbs?

- Could you directly observe whether a learner had reached this objective?

Now run the objectives through this Lesson Objective Advisor tool from the University of Manchester’s Faculty of Science and Engineering. Do the results match your assessment?

- Where do the skills described in these objectives sit on the scale?

- (optional) Are these objectives realistic, given the target audience of the lesson?

Advertising your lesson

These learning objectives, as well as the list of prerequisite knowledge you defined earlier, are very useful information to include when advertising a workshop that will teach your lesson. It will help people understand whether or not the event is a good fit for them, and manage their expectations about what they will learn if they attend.

If you are ending day 1 of the training here, this would be a great time to remind trainees that they should have reviewed the content of the Choosing a Narrative and Dataset for a Lesson in the community handbook. Trainees will need to apply the guidance on that page to the first exercise in the next episode.

- Defining objectives for a lesson can help to focus your content on the most important outcomes, and outline the scope of the project.

- Following the SMART framework can help make your learning objectives as useful as possible.

- Leaving objectives unrealistic or undefined increases the risk of a lesson losing focus or spending time on activities that do not help learners gain the most important skills.

Content from Example Data and Narrative

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why should a lesson tell a story?

- What considerations are there when choosing an example dataset for a lesson?

- Where can I find openly-licensed, published data to use in a lesson?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Find candidate datasets to use in a lesson.

- Evaluate the suitability of a dataset to be used in a lesson.

- Choose examples that will prepare learners for formative assessments in the lesson.

- Develop a story for their lesson

With your high-level lesson objectives set, now is a good time to consider any additional resources you may need to effectively communicate your message to learners before you dive deeper into writing the lesson content.

Writing your lesson as a story helps learners stay motivated and engaged, which means they will learn faster1. The story you create can also help learners more easily connect how the skills they are learning now could be useful after the workshop. You can enable learners to make connections between what they learn in your lesson and their own work, by creating a narrative that resembles a situation the learners might encounter there.

For a lot of lessons developed in The Carpentries community, the narrative is closely tied to the example data used in the lesson. A good example dataset makes it easier to teach the relevant skills, helps learners manage their cognitive load by focusing on what is most important. Just like the narrative, finding the right dataset involves striking a balance between authenticity and clarity.

Exercise: Choosing a Dataset or Narrative (30 minutes)

Referring to the advice you reviewed before this training, find an appropriate dataset or a narrative for your lesson. Identify one or more potential candidates and note down the advantages and disadvantages of each one.

As a summary, here are some aspects we suggest that you consider:

- For datasets:

- size

- complexity

- “messiness”/noise

- relevance to target audience

- availability

- license

- ethics

- For narratives:

- authenticity

- relevance to target audience

- complexity

- possibility to teach useful things first/early

Takes notes in your Lesson Design Notes document about your discussion and the decisions made. It may be particularly helpful to record:

- Which datasets and narratives did you consider?

- How and why did you choose between them?

- What implications do you think your choice of dataset and/or narrative will have for the design and further implementation of your lesson?

Summary

Remember, even if you do not need a dataset for your lesson, you should decide on a narrative. Building your lesson around a central example reduces the cognitive load of context switching throughout the lesson. Using an authentic, yet simple, dataset will also help reduce cognitive load and help learners to see how they might apply what they learned to their own projects. It is also important to consider licensing and ethical considerations when looking for a lesson dataset.

- Using a narrative throughout a lesson helps reduce learner cognitive load.

- Choosing a dataset includes considering data license and ethical considerations.

- Openly-licensed datasets can be found in subject area repositories or general data repositories.

The evidence for this is summarised well in chapter 3, What Factors Motivate Students to Learn?, of Ambrose et al. 2010. The Carpentries Instructor Training curriculum also includes a helpful summary of how lesson content can influence Learner motivation.↩︎

Content from Episodes

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 65 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can the objectives for a lesson be used to break its content into sections?

- How should objectives be written for a smaller part of a whole lesson?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- identify appropriate parts of their lesson to break into individual sections

- define learning objectives for a section of a lesson.

So far, you have defined the learning objectives for your lesson as a whole, and came up with a narrative or example datasets that will help you tell your story.

Rather than write the lesson as a single, long document, we recommend that you break it up into chunks like chapters in a book or episodes in a season of a TV series. This can help manage learners’ cognitive load by ensuring that you organise content into coherent, more self-contained chunks, and makes it easier for instructors to schedule regular and frequent breaks while teaching. Thinking about how content can be broken down like this early in the lesson design process helps you to consider the path learners will take to reach your defined objectives, and identify the component skills and knowledge they will need to pick up on the way.

In The Carpentries, we refer to these individual parts of a lesson as episodes, to encourage lesson developers to think about them as self-contained units (with their own narrative arc) that nevertheless contribute to the larger whole (the theme or story that runs through a full season). It also helps to think about the typical length of an episode: these chunks contain 20-60 minutes of content (teaching + exercises).

Each episode will exist as a page in the website we will build for our lessons.

Planning Your Episodes

Before we can start creating the episodes of a lesson, we need to spend some time planning out the number and order of them. The learning objectives you defined for your lesson can help with this: at the very least, it is probably a good idea to have one episode dedicated to each objective. You might also find that you can “decompose” the lesson-level objectives into more finely-grained steps that learners can take towards those end points. For example, the lesson-level objective

- “create formatted page content with Markdown”

may be broken down into,

- “create bold, italic, and linked text with Markdown”

- “explain the different header levels in Markdown”

- “add images with a caption and alternative text description to a Markdown document”

Some questions you might ask yourself to help break down your lesson-level learning objectives include:

- What new knowledge and skills will learners need to acquire to be ready to fulfil the overall objectives for your lesson?

- What order should these concepts and skills be introduced in? Are some dependent on others?

- If some of these concepts and skills are complex, can they be broken down even further?

Exercise: Defining Episodes for a Lesson (25 minutes)

With your team, in the shared notes document for your lesson:

- Based on the lesson-level objectives and your knowledge of the lesson topic, divide the lesson up into logical blocks (episodes), that should each take approximately 20-60 minutes to teach. Think of these logical blocks as topics that you need to cover within your lesson but do not go too deep into defining learning objectives for individual episodes - we will cover that soon.

- Next, assign responsibility for one of these episodes to each collaborator in your team. They will focus on this episode for the rest of this training.

Some questions you might ask yourself to help break down your lesson-level learning objectives include:

- What new knowledge and skills will learners need to acquire to be ready to fulfil the overall objectives for your lesson?

- What order should these concepts and skills be introduced in? Are some dependent on others?

- If some of these concepts and skills are complex, can they be broken down even further?

If the length of the list of episodes you create is smaller than the number of collaborators you have on your team, try assigning two people to a single episode, with each taking responsibility for a subset of the objectives defined for that episode. If you plan more episodes than you have people in your team, do not assign more than one episode to each collaborator for now, but we strongly recommend that you assign yourselves consecutive episodes at the beginning of your lesson.

Defining Episode-level Learning Objectives

Now that we have broken those lesson-level learning objectives into episodes, we can use the same approach for the individual episodes of a lesson, defining objectives for the episode to make clear what we intend to teach in that section. Defining these objectives before writing the episode content helps us to:

- stay focused in the episode, without spending time on non-essential topics

- determine whether learners are attaining the skills we wish to teach them (we will discuss this more in the next two episodes)

- summarise the skills the learner can expect to gain by following this section of the lesson

As before, here are some recommendations to help you define these episode-level objectives:

- Aim for 2-4 objectives per episode. If you need to write more than that, consider breaking this section down into multiple episodes.

- To ensure your episode content aligns with the overall goals for the lesson, try to identify which lesson-level objective(s) your episode will contribute to.

- In the context of the previous recommendation, consider how the objectives for your episode fit as a component of the higher-level skills/understanding defined in the lesson-level objective(s).

Exercise: define objectives for your episode (30 minutes)

- Using the same approach as you did for your whole-lesson objectives, define a set of SMART objectives for your chosen episode. (15 minutes)

- Compare your list with those created by your collaborators on the

lesson:

- are there any gaps in these objectives, i.e. anything that should be covered in these episodes but is not captured in the objectives?

- are there any overlaps, i.e. anything that looks like it will be covered more than once?

- As a group, discuss how you will address any problems identified in the previous step, and edit your objectives accordingly.

Optional Homework: Reflection Exercise (not included in timing)

Take some time to think back on what has been covered so far, then make some notes on the most important points and actions you want to take away from that. The Trainers and other participants will not look at this - it is only for you.

If you do not know where to start, consider the following list for a starting point:

- draw a concept map, connecting the material

- draw pictures or a comic depicting one of the concepts covered

- write an outline of the topics we covered

- write a paragraph or “journal” entry about your experience of the training today

- write down one thing that struck you the most

- Learning objectives for a lesson can help you split up its content into chunks

Content from Designing Exercises

Last updated on 2025-11-21 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 80 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can you measure learners’ progress towards your lesson objectives?

- Why are exercises so important in a lesson?

- What are some different types of exercises, and when should they be used?

- Why should we create assessments before we have written the explanatory content of our lesson?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Describe the importance of regular exercises while a lesson is being taught.

- Choose the format for an exercise based on the outcome it is intended to measure.

As we have seen previously, defining objectives for a lesson (or a teaching episode) can help to focus your content on the most important learning outcomes and outline the scope of your lesson project. The goal of the remaining steps of lesson development is to ensure that what learners learn from following your lesson matches its defined objectives as closely as possible. To do this, you need to develop assessments to monitor progression towards your learning outcomes.

Useful further reading: Course design: Considerations for Trainers – a Professional Guide.

Assessments

In order to measure progress and evaluate if and what learning occurred, we have various types of assessment available to us:

- summative assessments - used after instruction to verify whether learners achieved the stated learning objectives.

- formative assessments - used during instruction to detect changes in learner understanding or performance, to provide feedback and insight (to both instructors and learners) into the learners’ developing mental models of the topic taught and to identify any old or developing misconceptions.

Summative assessments sum up what learning has been achieved after training (e.g. via exams). They give valuable data about learning attainment by individuals and entire cohorts but are not used to guide further progress of a lesson. They may not be as suitable for short courses, but may be necessary for those that give marks/grades or certificates of completion.

Formative assessments are applied throughout a course and with several different purposes: they provide a way to move new information from working memory to long-term memory; they can inform instructors’ decisions about how to modify instruction to better promote learning; they also inform learners about changes they may need to make to improve their learning. Ideally, they should be used often (e.g. after every 15-20 minutes of teaching), providing opportunities to instructors to change pace and refocus learners’ attention. For short courses, formative assessments are usually more valuable and easier to implement in practice than summative assessments - they need not be complex or time-consuming, just informative enough about learning for both instructors and learners.

The most effective way to test learner understanding and progress is to do such assessments in class - they engage all learners and allow instructors to check learners’ confidence with the content and its delivery, can help you deal with any potential misunderstandings as soon as they arise, and maximise the value of the workshop for everyone. Such formative assessments also help with metacognition - the awareness a learner has about how their learning is progressing.

Any instructional tool that generates feedback and is used in a formative way to check for learners’ understanding can be described as “formative assessment”. For example,

- checking in - gauging learners’ satisfaction and understanding using agreed signals (e.g. raising different coloured post-it/sticky notes or Zoom reactions to indicate that the pace is too fast/slow, or that they completed/have not completed an exercise).

- group or collaborative discussions - raising questions for discussion among the group. For example, think, pair, share, where learners think individually about an answer to a question, pair up with a classmate to discuss their answer, and then share out the consensus they came to with the class.

- problem-solving or diagnostic exercises - setting (coding or non-coding) challenges for learners to tackle, testing comprehension of a subject and diagnosing any forming misconceptions (e.g. via multiple choice questions).

- individual (guided) reflections at the end of a session to help process what was learned, for example asking learners to write down, draw, or diagram things they learned, noting how things relate to one another or connect with previous knowledge, things they want to know more about, and any questions they still have.

Many other formative assessment tools can be found in Briggs’ list of “21 ways to check for student understanding” or Edutopia’s “56 Examples of Formative Assessment”.

Formative Assessments in this Training (5 mins)

Think back through the parts of this training you have followed so far. Identify two examples of formative assessment that the Trainers have employed. As an extra challenge, try to decide whether these assessments were used to assess progress towards a particular learning objective and, if so, what the relevant objective might have been.

Some examples of formative assessments used so far in this training:

- Exercises such as the one asking trainees to describe the target

audience of their lesson

- this exercise aims to assess how well trainees are able to identify the aspects of a target audience that influence the design of a lesson. It also aims to expose any inconsistencies between the visions of the target audience held by different collaborators.

- Your Trainers have probably checked in with the group at various

points in the training.

- Although these check-ins are not specific to a particular objective, they help give us an impression of how well trainees are able to follow what we are teaching.

- Tracking the progress of your lesson

repository configuration on GitHub.

- This helps us evaluate trainees’ progress towards the learning objectives we have set in relation to the lesson infrastructure.

Exercise Learners’ Memory

In a simplified model of memory, individuals are equipped with two types of memory: working (also called short-term) and long-term. Long-term memory essentially has unlimited storage but is slow to access, whereas working memory is quicker to access but can only hold a limited number of items at a time. For teaching, the goal is to help learners move the new things they’ve learned from working memory into long-term memory. Exercises help with this by providing learners an opportunity to practice what was recently learned. Exercises should occur frequently throughout the lesson to free up working memory and make space for more new information.

Creating exercises builds upon the learning objectives you created earlier in the lesson design process. You can design exercises based on the skills you described in your learning objectives (the learning outcomes you intend for the lesson). This will be easier if your wrote learning objectives with specific action verbs. Specific verbs can help you decide what action you want the learners to perform in the exercise. E.g. actions such as “explain” and “describe” may be better assessed by discussions and multiple choice questions, while “solve,” “construct,” “test” and other higher-level cognitive skills may be better assessed by debugging tasks, code-and-run, or use-in-a-different-context exercises.

Exercise: Exercise Types and When to Use Them (15 minutes)

The Trainers will assign you to pairs or small groups, and give each group an exercise type to work on. Each group should assign a notetaker, to summarise your discussion at the end of the exercise.

The Trainers will assign your group a type of exercise to focus on. Read about your given exercise type in the Exercise Types chapter of Teaching Tech Together by following the relevant link below.

(A Spanish version of Teaching Tech Together is also available.)

Then, considering the exercise type in general, as opposed to the specific example given in the text, discuss the following questions together:

- What kind of skills would an exercise of this type assess? Try to identify some action verbs like those we used to write lesson objectives earlier in the workshop (you may refer to the extended Bloom’s taxonomy for computing to help you).

- Would this type of exercise be suited to a novice audience? Or is it a better fit for intermediate or advanced learners?

- Would this kind of exercise work well in an in-person workshop setting? Would it be better suited to self-directed learning and/or a virtual workshop?

Share the major points of your discussion in the collaborative notes document.

The Trainers will assign your group a type of exercise to focus on. Read about your given exercise type on the indicated pages of Is This a Trick Question?:

- multiple choice (page 13)

- true-false (pages 20 & 21)

- fill-in-the-blank (page 34)

- authentic assessment (pages 46 & 47)

Then, discuss the following questions together:

- Could exercises of this type be used in your lesson?

- If so, can you identify any of your written objectives that could be assessed with an exercise of this type?

- Have your Trainers set you any exercises of this type in this training so far?

- Would this type of exercise be suited to a novice audience? Or is it a better fit for intermediate or advanced learners?

- Would this kind of exercise work well in an in-person workshop setting? Would it be better suited to self-directed learning and/or a virtual workshop?

Exercise: Exercise Types and When to Use Them (15 minutes) (continued)

Trainers will lead a discussion about your findings for your chosen exercise type with the rest of the participants.

Both of the resources linked from the exercise above, the Exercise Types chapter of Teaching Tech Together and Is This a Trick Question? (ref) are worth reading in full. They collect a lot of insightful discussion and illustrative examples, which can prove very useful when designing exercises for your lesson.

As you discussed with your group in the last exercise, different types of learning objectives work better for novices, while others are a better fit for competent practitioners or experts.

This can be understood in terms of the types of exercises that suit the objective: exercise types that help manage cognitive load for the learner, such as fill-in-the-blanks, faded examples or Parsons problems (which all provide a lot of the guiding process/scaffolding code and allow the learner to focus on a specific concept or skill) are a good fit for a novice, to whom all elements of the topic are new. However, these kinds of exercise do not provide an opportunity for learners to develop higher-level skills, such as the ability to create whole new functions or scripts, or to extrapolate from the examples they have seen to solve a different kind of problem. Indeed, example and exercise types that are helpful to novices may even be counter-productive for learners with a greater level of expertise1.

Thus you want to choose your objectives to fit your intended audience and your exercise formats to fit your objectives.

An Expert’s View on Objectives and Audience Expertise

“Different types of lesson objectives (LOs) are better fit for novices, while others are better fit for competent practitioners, etc. and if exercises (formative assessments) are well aligned to LOs, [they] will automatically serve the corresponding audience. Thinking in terms of LOs (What should a learner do in order to achieve this specific LO? Is this LO exactly what learners are expected to achieve by the end of this piece of instruction? etc.) is easier than thinking in terms of LOs + audience + content. LOs should be tailored to the audience, and, if this is well done, you may stop worrying about the audience. Create LOs for the specific audience and create assessments for specific LOs.”

- Dr. Allegra Via, Carpentries Instructor Trainer

Detecting and correcting misconceptions and fixing learners’ incorrect/broken mental models is as important as presenting your learners with new knowledge and correct information. When mental models are broken, learning can occur more slowly than you might expect2. The longer a prior incorrect model is in use, and the more extensively it has to be “unlearned”, the more it can actively interfere with the incorporation of the new correct knowledge (since it will contradict the misconceptions already present in the mental model).

When designed well, multiple choice questions can diagnose misconceptions you predict that learners might have, and help you correct them quickly.

We recommend that you read the sections of the Instructor Training curriculum and Teaching Tech Together linked above. You may also find it interesting and helpful to review our supplementary page digging into misconceptions and multiple choice questions in more detail.

Exercise: Assessing Progress Towards an Objective (30 minutes)

Using one of the exercise formats you have learned about so far, design an exercise that will require learners to perform one of the actions described in the objectives you wrote earlier, and that assesses their ability to do so.

These should be assessments of the lower-level objectives defined for individual episodes in the lesson, as opposed to the lesson-level objectives you wrote first.

Trainees working as a team can choose whether to work together on discussing and designing a single exercise to assess a single objective, or to divide their efforts and each focus on an exercise for their own episode. If you choose to take the latter approach and finish with time to spare, spend the remainder reviewing and providing feedback on one another’s assessments.

The same approach to designing exercises within a lesson can also be used to create a short “pre-assessment” questionnaire for potential learners to complete when they register for a workshop teaching the lesson (or for self-evaluation before following the lesson on their own). You can use the list of prerequisite knowledge that you defined earlier to help with this.

If you collect the results of this questionnaire, use it to follow up with people who have registered for the workshop but do not fit the intended target audience, to manage their expectations about how useful the workshop will be for them.

You should aim to create all your assessments before you write the explanatory content of your lesson (recall Nicholls’ backward design). These assessments will guide your lesson design process by making sure you know exactly what knowledge you’d expect from your learners at any point in the lesson.

Well-designed exercises are one of the most valuable resources for an instructor and any time spent on this during lesson design is well invested.

- Assessments are a way to determine whether the objectives you defined for the lesson have been reached.

- Exercises help learners commit what they’ve learned to long-term memory.

- Some types of exercises are better for particular audiences and to address certain objectives.

- Formative assessment happens during teaching and provides feedback both to an instructor and a learner - about progress and whether learning of new concepts occurred but also about any misunderstandings and misconceptions which can hinder further learning.

See chapter 1, How Does Students’ Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?, of Ambrose et al. 2010.↩︎

See chapter 1, How Does Students’ Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?, of Ambrose et al. 2010.↩︎

Content from How to Write a Lesson

Last updated on 2025-11-24 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 70 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why do we write explanatory content last?

- How can I avoid demotivating learners?

- How can I prioritise what to keep and what to cut when a lesson is too long?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Estimate the time required to teach a lesson.

- Summarise the content of a lesson as a set of questions and key points.

- Connect the examples and exercises in a lesson with its learning objectives.

Writing Explanatory Text

Explanatory text (including examples) help connect your exercises together into a cohesive lesson. If your exercises are train stations and scenic views, the explanatory text is the train tracks that connect them. Often times the examples and exercises may seem like a good draft for you to teach. However, the explanatory text makes it possible for other instructors and self-directed learners to follow along by providing all the relevant information directly in the lesson. It can also help you remember your goals and stay on track teaching.

How much text to include is often a question of personal style while balancing the needs of potential users, both other instructors and learners. You want to find the balance between providing enough information for learners to meet the learning objectives without increasing cognitive load with extraneous information. In this section we will discuss factors to consider when you are writing explanatory text.

There are trade-offs to consider when preparing a site for use as an instructional guide vs use as a self-directed learning resource. Typically, self-directed learning resources are more verbose where instructional guides are aimed at an audience that can fill in the gaps on their own. However, very sparse text is less likely to be re-usable by other instructors as instructors may have different skill levels with the lesson content or differing mental models. In general, it is not a good idea to assume others, learners or instructors, will know what you were thinking when you wrote the content so, if in doubt, be explicit.

Exercise: Examples Before Exercises (20 minutes)

Looking back at one of the exercises you designed before: what examples could you include in your narrative to teach learners the skills they will need to apply to complete the formative assessments you have designed?

Outline one of these examples in your lesson design notes.

In the Software Carpentry Plotting and Programming with Python Lesson there is an exercise to load and inspect CSV file for Americas. In the lesson, before the exercise, the Instructor demonstrates an example of how to load the data table for another continent (Oceania) and explores the values with a few different functions. This shows learners how to call the function to load the CSV into a data frame, and demonstrates what success looks like for their exercise.

In the Python Interactive Data Visualization Lesson in the Incubator, there is an exercise to find the correct widget (a slider) for an action and modify the script to use it. In the lesson, before the exercise, the instructor introduces a cheatsheet and documentation for interactive widgets and then creates a dropdown widget for the application. The slider widget required in the exercise has not been demonstrated but the preceding example shows all of the necessary steps to add a widget, and provides the supporting information that learners can consult to discover how to implement the specific tool.

Less is More

Trying to fit too much content into a lesson is counter-productive. It is better to cover less and provide a smaller but stable foundation for learners to build upon.

You should also consider a realistic workshop length for teaching your lesson. It is difficult to keep learners attentive for many hours over many days. Most Carpentries workshops are two work days of lesson material as it is difficult for learners to attend 4 full days of a workshop. Although, there are some in the community who will run workshops that are three days to cover additional material.

As you consider the length of your lesson discuss with your collaborators and ask yourself:

- What is essential to include?

- What can be left out if needed?

- Are there checkpoints where the lesson could end if needed?

- Can important concepts be moved up earlier to ensure they are covered?

In the end, the only way to know for sure is to teach the lesson, measuring how long it takes to teach. Borrowing from television, The Carpentries community calls these early workshops, pilot workshops. As you run pilot workshops, you can note the length of time spent in each episode. Instructors commonly report running short on time in workshops. Thus, it is better to assume that you are under-estimating rather than over-estimating the length. It is better to have additional time for discussion, review, and wrap-up than to rush through material to fit it into the remaining time.

If, after piloting your new lesson, you find that you did not have time to cover all the content, approach cutting down the lesson by identifying which learning objectives to remove. Then take out the objective(s) and the corresponding assessment(s) and explanatory content. You may consider making a concept map to help identify which objectives depend on one another.

Alternatively, if you decide to keep certain objectives in the lesson, you can add suggestions on which objectives can be skipped to the Instructor Notes for the lesson. Instructor Notes are meant to convey teaching tips and advice to other instructors teaching your lesson and will be discussed in more detail later on in section “Preparing to Teach”.

As you add notes and think about what to cut, remember, reducing the number of lesson objectives can help with managing learner (and instructor) cognitive load.

“the five ways to handle an extraneous overload situation are to:

- eliminate extraneous material (coherence principle),

- insert signals emphasizing the essential material (signaling principle),

- eliminate redundant printed text (redundancy principle),

- place printed text next to corresponding parts of graphics (spatial contiguity principle), and

- eliminate the need to hold essential material in working memory for long periods of time (temporal contiguity principle).”

Lesson Time Management (10 minutes)

(5 minutes) In the shared notes document, note down your answers to these questions:

- Most people have experienced a workshop or another event where there

was too much material to cover in the time available.

- In what ways have you observed event facilitators and instructors respond to these circumstances?

- How did this affect your experience as a learner/participant?

- Can you recall any strategies that have worked particularly well?

- What are some advantages and disadvantages for the learner when an instructor breaks up a lesson into smaller chunks over a longer time period?

(5 minutes) In the remaining time, your Trainers will lead a discussion based on the responses.

To get started on the discussion part, try reading out an interesting response and asking for more detail from the trainee who wrote it. Ask one of the other trainers/helpers to take notes of this discussion in the collaborative note-taking document.

This is a good opportunity to remind trainees about how counter-productive it can be to try to cover more content than the time allows. (See the earlier section on lesson scope.)

Other Important Considerations for Lesson Content

Language

When writing your lesson text you also want to avoid unintentionally demotivating your learners. Make time to review your text for:

- dismissive language - e.g. ‘simply’, ‘just’

- use of stereotypes (check learner profiles for stereotypes too)

- expert awareness gaps, i.e. places where you may be assuming the learners know more than they actually do

- use of different terms or notations with the same meaning interchangeably without explanation, e.g. using the terms “shell”, “bash”, “terminal” and “console” to describe the command line interface, or “variables” and “columns” for column headings in data tables

- unexplained or unnecessary jargon/terminology (as your learners may come from different backgrounds, may be novices, not native English speakers, and a term in one domain/topic may mean something else entirely in another)

- unexplained assumptions

- sudden jumps in difficulty/complexity

You may want to check out Julia Evans’ blog post on “Patterns in confusing explanations” to help review your explanatory text for common patterns in language that can make your explanatory text confusing.

Accessibility

You should also review your text thinking about accessibility. This includes:

- Avoiding regional/cultural references and idioms that will not translate across borders/cultures

- Avoiding contractions i.e. don’t, can’t, won’t etc.

- Checking that all figures/images have well written alternative text, including writing alternative text for data visualizations. An alternative text contains an invisible description of an image which is read aloud to blind users by screen readers providing alternative text-based format for images. See the Workbench documentation for directions on how to add alternative text and captions to images in a lesson

- Checking the header hierarchy - no h1 headers in the lesson body, no skipped levels

- Using descriptive link text - no “click here” or “this page”, etc.

- Checking the text and foreground contrast for images

Optional Exercise: Alternative Text for Images (5 minutes)

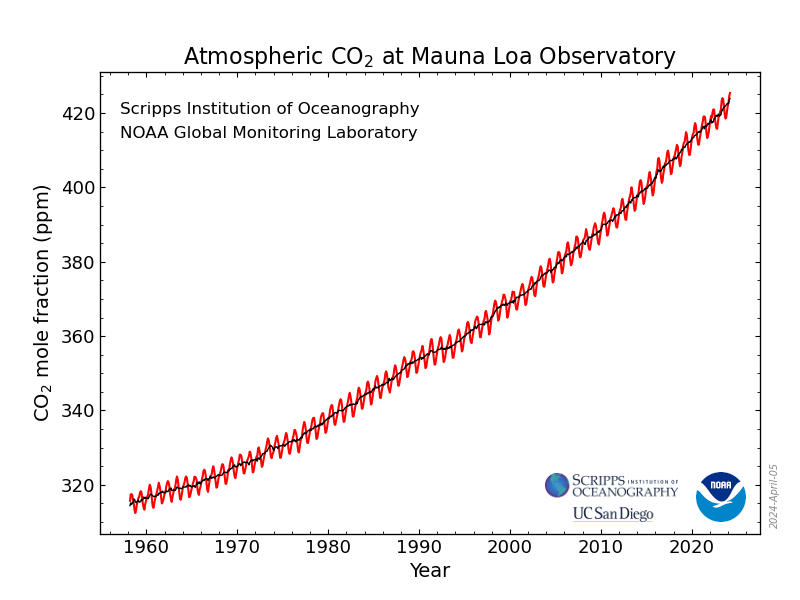

Which of the following is a good alt-text option for the image below?

- Graph of data

- Graph with increasing lines

- Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory from 1958 to present

- Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, United States, from 1959 to present including values from each year. Red line shows variation in each year and black line is average for each year. 1959 = 315.90 ppm, 1960 = 316.91, 1961 = 317.64 …

Data/Image provided by NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, Boulder, Colorado, USA

The third option, “Line graph of increasing carbon dioxide in ppm at the Mauna Loa Observatory from 1958 to present”, is the best option. It describes the type of plot, what is measured, and the trend.

The first two options are too vague. They mention a graph but don’t give enough info to know what the graph is actually showing.

The last option is overly descriptive and starts to list the data itself. It is better to include a shorter, but informative, description and a link to the data instead.

May want to point out that the answers in the current version of this exercise do not have diagnostic power.

Glossary of Terms

When writing a lesson, you should also consider adding key terms or jargon to the lesson glossary for the lesson. In your shared notes document, you can start such a glossary as you develop your lesson, to keep a record of the terminology your audience needs to be familiar with.

Many of these terms may also be useful for other lessons and can be added to Glosario, a multilingual glossary for computing and data science terms.

Exercise: Explain Your Terminology (5 minutes)

In your shared notes document, add a list of terms or jargon from your lesson, along with their definitions.

You do not have to have a complete list now, but it is good to start working on it - you can always come back and update it later.

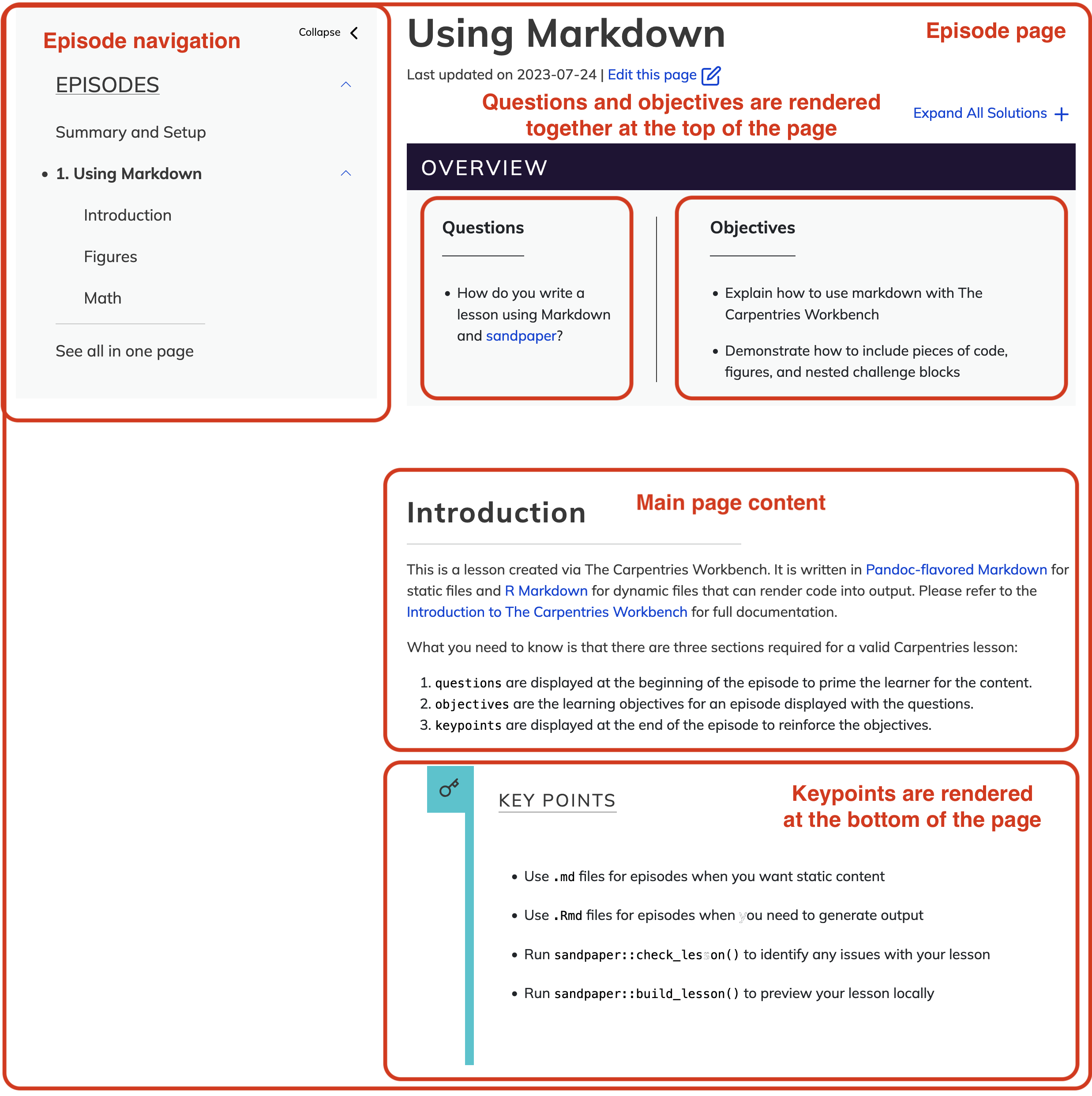

Questions and Keypoints

In addition to objectives, a completed episode also requires questions the episode answers and the keypoints a lesson covers.

The questions helps learners understand what to expect from a lesson as they might not yet understand the learning objectives.

The keypoints wrap up the lesson by providing answers to each of the questions. Keypoints also help self-directed learners review what they learned, remind instructors to recap what was covered in an episode, and help you ensure you answered all the questions you intended for an episode.

Exercise: Completing episode metadata (10 minutes)

In your shared notes document, add key points and questions for your episode.

Polishing a lesson

Lessons do not need to be perfected prior to teaching them the first time. In fact, keeping things relatively basic leaves you some flexibility while you run through the first few iterations of teaching the lesson, collecting feedback, and using that to guide improvements.

However, once you find that the lesson is beginning to reach something like a stable state, you may find the checklist for lesson reviewers in The Carpentries Lab useful as a guide for polishing the design and content. The checklist describes criteria for a lesson to meet a high standard in terms of its accessibility, design, content, and supporting information.

- The objectives and assessments provide a good outline for an episode and then the text fills in the gaps to support anyone learning or teaching from the lesson.

- It is important to review your lesson for demotivating language, cognitive load, and accessibility.

- To reduce cognitive load and ensure there is enough time for for the materials, consider which lesson objectives are not needed and remove related content and assessments.

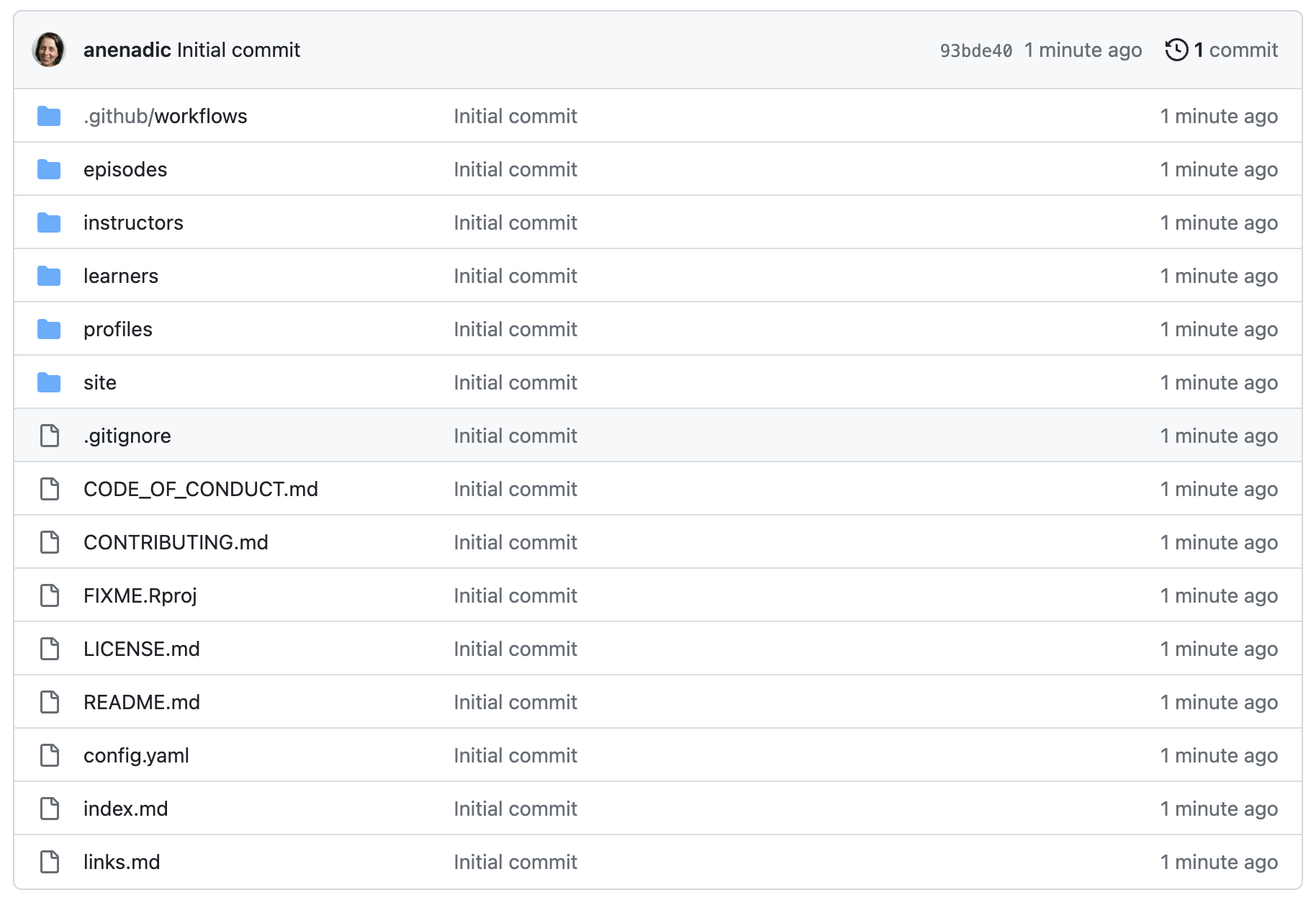

Content from The Carpentries Workbench

Last updated on 2025-05-02 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 70 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How is a lesson site set up and published with GitHub?

- What are the essential configuration steps for a new lesson?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Identify the key tools used in The Carpentries lesson infrastructure.

- Complete the fundamental setup steps for a new lesson repository.