Episode Structure

Last updated on 2026-02-28 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do you create a new episode?

- What syntax do you need to know to contribute to a lesson with The Carpentries Workbench?

- How do you write challenge blocks?

- What syntax do you use to write links?

- How do you include images?

- How do you include math?

- How do you include Glosario terms?

Objectives

- Practise creating a new episode with R

- Understand the required elements for each episode

- Understand pandoc-flavored markdown

- Demonstrate how to include pieces of code, figures, and nested challenge blocks

Introduction

An episode1 is an individual unit of a lesson that focuses on a single topic with clear questions, objectives, and key points. If a lesson goal is to teach you about using git, an individual episode would teach you how to inspect the status of a git repsitory. The idea behind the name “episode” is the thought that each one should last about as long as an episode for an television series.

As we will cover in the next episode, all

of the episodes live inside the episodes/ directory at the

top of the lesson folder. Their order is dictated by the

episodes: element in the config.yaml file (but

defaults to alphabetical). The other folders (learners/,

instructors/, and profiles/) are similarly

configured. This episode will briefly explain how to edit markdown

content in the lessons.

Buoyant Barnacle

The exercises in this episode correspond to the Buoyant Barnacle repository you created in the Introduction

There are three things you should be comfortable with in order to contribute to a lesson 2

- Writing basic and extended markdown syntax

- Writing Fenced div elements to create callouts and exercise blocks

- Writing simple yaml lists

Creating A New Episode

To create a new episode, you should open your lesson

(buoyant-barnacle) in your RStudio or your favorite text

editor and in the R console type:

R

sandpaper::create_episode("next-episode")

This will create a new episode in the episodes folder called

“02-next-episode.Rmd”. If you already have your episode schedule set in

config.yaml, then this episode will not be rendered in the

site and will remain a draft until you add it to the schedule. Next, we

will show how you can add a title and other elements to your

episode.

What is the .Rmd extension?

You might notice that the new episode has the extension of

.Rmd instead of .md. This is R Markdown, an

extension of markdown that allows us to insert special code fences that

can execute R code and automatically produce output chunks with controls

of how the output and input are rendered in the document.

For example, this markdown code fence will not produce any output, but it is valid for both Markdown and R Markdown.

R

print("hello world!")

But when I open the fence with ```{r} then it becomes an

R Markdown code fence and will execute the code inside the fence:

R

print("hello world!")

OUTPUT

[1] "hello world!"Note that it is completely optional to use these special code fences!

Required Elements

To keep with our active learning principles, we want to be mindful about the content we present to the learners. We need to give them a clear title, questions and objectives, and an estimate of how long it will take to navigate the episode (though this latter point has shown to be demoralizing). Finally, at the end of the episode, we should reinforce the learners’ progress with a summary of key points.

YAML metadata

The YAML syntax of an episode contains three elements of metadata associated with the episode at the very top of the file:

YAML

---

title: "Using RMarkdown For Automated Reports" # Episode title

teaching: 5 # teaching time in minutes

exercises: 10 # exercise time in minutes

---

## First Episode SectionCreate a Title

Your new episode needs a title!

- Open the new episode in your editor

- edit the title

- add the episode to the

config.yaml - preview it with

sandpaper::build_lesson()or using the ctrl + shift + k keyboard shortcut.

Did the new title show up?

Questions, Objectives, Keypoints

These are three blocks that live at the top and bottom of the episodes.

-

questionsare displayed at the beginning of the episode to prime the learner for the content -

objectivesare the learning objectives for an episode and are displayed along with the questions -

keypointsare displayed at the end of the episode to reinforce the objectives

They are formatted as pandoc fenced divisions, which we will explain in the next section:

Optional Elements

Lessons do not have to contain the following structural elements, but they can be useful for highlighting particular content.

Callout blocks

One of the key elements of our lessons are our callout blocks that give learners and instructors a bold visual cue to stop and consider a caveat or exercise. To create these blocks, we use pandoc fenced divisions, aka ‘fenced-divs’, which are colon-delimited sections similar to code fences that can instruct the markdown interpreter how the content should be styled.

Callout Component Guide

You can find a catalogue of the different callout blocks The Workbench supports in The Workbench Component Guide.

For example, to create a callout block, we would use

a blank line and at least three colons followed by the

callout tag (the tag designates an open fence), add our

content after a new line, and then close the fence with at least

three colons and no tag (which designates a closed fence):

This is a callout block. It contains at least three colons

However, it may be difficult sometimes to keep track of a section if it’s only delimited by three colons. Because the specification for fenced-divs require at least three colons, it’s possible to include more to really differentiate between these and headers or code fences:

MARKDOWN

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: testimonial

I'm **really excited** for the _new template_ when it arrives :grin:.

--- Toby Hodges

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::I’m really excited for the new template when it arrives 😁.

— Toby Hodges

Even better, you do not have to worry about counting colons! It doesn’t matter how many colons you put for the opening and closing fences, all that matters is you can visually see that the fences match.

That’s right, we can use emojis in The Carpentries Workbench! 💯 🎉

Tabbed content

Available from varnish v1.0.2, tabs are a great way to present

multiple pieces of information in a compact and organised way. You can

create them in two ways: firstly with a tab fenced div, and

secondly with a group-tab fenced div.

Whilst they both show content in the same way, grouped tabs differ from standard tabs in that they remember which tab you have selected across page changes. This can be useful if you want to use a specific tab throughout the lesson content, e.g. for a set of exercises or a set of solutions you want to use the “Windows” tab that was initially selected in the Setup episode.

The first tab specified is the default tab.

In both cases, tabs can hold callouts themselves and be specified within callouts too!

Tab

To create a tab group, create a tab fenced div, and then

add a level 3 markdown heading (###) for each tab you want

to create:

MARKDOWN

::: tab

### Windows

Some Windows instructions

### Mac

Maybe some for Mac

### Linux

And more for Linux users, including a code block:

```python

print("Yay, tabs!")

```

:::Grouped tabs

Much like standard tabs, to create grouped tabs use a

group-tab fenced div, and then add a level 3 markdown

heading (###) for each tab you want to create:

MARKDOWN

::: group-tab

### Windows

1

### Mac

2

### Linux

3

:::

::: group-tab

### Windows

4

### Mac

5

### Linux

6

:::The first tab specified is the default tab.

In the example below, selecting a tab in one tab group changes the tab in the other group(s).

(Thanks to @astroDimitrios for this great feature!)

Instructor Notes

The Carpentries Workbench supports separate instructor/learner views,

which allows for instructor notes to be incorporated into the lesson.

The default view of a lesson is the learner view, but you can switch to

the instructor view by scrolling to the top of the lesson, clicking on

the “Learner View” button at the top right, and then selecting

“Instructor View” from the dropdown. You can also add

instructor/ after the lesson URL (e.g. in this lesson, the

URL is

https://carpentries.github.io/sandpaper-docs/episodes.html;

to switch to the instructor view manually, you can use

https://carpentries.github.io/sandpaper-docs/instructor/episodes.html).

View the instructor note

When you visit this page, the default is learner view. Scroll to the top of the page and select “Instructor View” from the dropdown and return to this section to find an instructor note waiting for you.

MARKDOWN

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: instructor

This is an instructor note. It contains information that can be useful for

instructors to know such as

- **Useful hints** about places that need extra attention

- **setup instructions** for live coding

- **reminders** of what the learners should already know

- anything else

```markdown

You can also include _any markdown elements_ like `code blocks`

```

{alt='a random image of a cute kitten'}

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::Exercises/Challenges

The method of creating callout blocks with fences can help us create solution blocks nested within challenge blocks. Much like a toast sandwich, we can layer blocks inside blocks by adding more layers. For example, here’s how I would create a single challenge and a single solution:

MARKDOWN

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: challenge

## Chemistry Joke

Q: If you aren't part of the solution, then what are you?

:::::::::::::::: solution

A: part of the precipitate

:::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::Chemistry Joke

Q: If you aren’t part of the solution, then what are you?

A: part of the precipitate

To add more content to the challenge, you close the first solution and add more text:

Challenge 1: Can you do it?

What is the output of this command?

R

paste("This", "new", "template", "looks", "good")

OUTPUT

[1] "This new template looks good"Challenge 2: how do you nest solutions within challenge blocks?

You can add a line with at least three colons and a

solution tag.

Now, here’s a real challenge for you

Yes! It is a valid fenced div for the following reasons:

- The opening fence has ≥3 colons

- The opening fence has a class designation

- The closing fence is on its own line and has ≥3 colons

Use Spoilers Instead of Floating Solution Blocks

When not attached to a challenge div, a formatted

solution block will be displayed with too much “buoyancy”

i.e. floating too high and obscuring some of the preceding content.

To avoid this, use the spoiler class of fenced div for

expandable/collapsible blocks of details instead of a floating

solution.

Expandable “Spoiler” Blocks

It can be helpful to provide “accordion” blocks of content that can be expanded and collapsed with a mouse click in some circumstances e.g. to provide detailed instructions for different operating systems, which can be examined by users based on their own system setup.

Such blocks of content can be added to a page with the

spoiler class of fenced div:

MARKDOWN

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: spoiler

### What Else Might We Use A Spoiler For?

- including a collapsed version of a very long block of output/a large image from a code block,

which the learner can expand if they want to check their output against the lesson

- a reminder of some important concept/information required to follow the lesson,

that you expect only some learners will need to read

- wrapping a set of optional exercises for an episode

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::- including a collapsed version of a very long block of output/a large image from a code block, which the learner can expand if they want to check their output against the lesson

- a reminder of some important concept/information required to follow the lesson, that you expect only some learners will need to read

- wrapping a set of optional exercises for an episode

Code Blocks with Syntax Highlighting

To include code examples in your lesson, you can wrap it in three backticks like so:

Input:

Output:

thing = "python"

print("this is a {} code block".format(thing))To include a label and syntax highlighting, you can add a label after the first set of backticks:

Input:

Output:

To indicate that a code block is an output block, you can use the label “output”:

Input:

MARKDOWN

```python

thing = "python"

print("this is a {} code block".format(thing))

```

```output

this is a python code block

```Output:

OUTPUT

this is a python code blockThe number of available languages for syntax highlighting are numerous and chances are, if you want to highlight a particular language, you can add the language name as a label and it will work. A full list of supported languages is here, each language being a separate XML file definition.

Tables

Tables in The Workbench follow the rules for pandoc pipe table syntax, which is the most portable form of tables.

Because we use pandoc for rendering, tables also have the following features:

- You can add a table caption, which is great for accessibility3

- You have control over the relative width of oversized table contents

Here is an example of a narrow table with three columns aligned left, center, and right, respectively.

MARKDOWN

Table: Four fruits with color and price in imaginary dollars

| fruit | color | price |

| ------ | :--------------: | -------: |

| apple | :red_circle: | \$2.05 |

| pear | :green_circle: | \$1.37 |

| orange | :orange_circle: | \$3.09 |

| gum gum fruit | :purple_circle: | \$999.99 || fruit | color | price |

|---|---|---|

| apple | 🔴 | $2.05 |

| pear | 🟢 | $1.37 |

| orange | 🟠 | $3.09 |

| gum gum fruit | 🟣 | $999.99 |

You can see that we now have a caption associated with the table.

Table alignment best practises

The colons on each side of the - in the table dictate

how the column is aligned. By default, columns are aligned left, but if

you add colons on either side, that forces the alignment to that

side.

In general, most table contents should be left-aligned, with a couple of exceptions:

- numbers should be right aligned

- symbols, emojis, and other equal-width items may be center-aligned

These conventions make it easer for folks to scan a table and understand its contents at a glance.

Because it is a narrow table, the columns fit exactly to the contents. If we added a fourth, longer column (e.g. a description), then the table looks a bit wonky:

MARKDOWN

Table: Four fruits with color, price in imaginary dollars, and description

| fruit | color | price | description |

| ------ | :--------------: | -------: | ----------- |

| apple | :red_circle: | \$2.05 | a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day |

| pear | :green_circle: | \$1.37 | a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon |

| orange | :orange_circle: | \$3.09 | a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days |

| gum gum fruit | :purple_circle: | \$999.99 | a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers || fruit | color | price | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| apple | 🔴 | $2.05 | a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day |

| pear | 🟢 | $1.37 | a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon |

| orange | 🟠 | $3.09 | a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days |

| gum gum fruit | 🟣 | $999.99 | a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers |

If we want to adjust the size of the columns, we need to change the lengths of the number of dashes separating the header from the body (as described in pandoc’s guide for tables).

Notice how the pipe characters (|) do not necessarily

have to line up to produce a table.

MARKDOWN

Table: Four fruits with color, price in imaginary dollars, and description

| fruit | color | price | description |

| ---- | :-: | ---: | --------------------------- |

| apple | :red_circle: | \$2.05 | a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day |

| pear | :green_circle: | \$1.37 | a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon |

| orange | :orange_circle: | \$3.09 | a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days |

| gum gum fruit | :purple_circle: | \$999.99 | a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers || fruit | color | price | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| apple | 🔴 | $2.05 | a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day |

| pear | 🟢 | $1.37 | a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon |

| orange | 🟠 | $3.09 | a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days |

| gum gum fruit | 🟣 | $999.99 | a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers |

Adjust column widths

Adjust the widths of the columns below so that the columns are around a 1:5:1 ratio with the second column having center-justification:

MARKDOWN

Table: example table with overflowing text in three columns

| first | second | third |

| ----- | ------ | ----- |

| this should be a small, compact column | this should be a wide column | this column should also be small and compact, much like the first column || first | second | third |

|---|---|---|

| this should be a small, compact column | this should be a wide column | this column should also be small and compact, much like the first column |

To get a roughly 1:5:1 ratio, you can use two separators for the short columns and ten separators for the wide column:

MARKDOWN

Table: example table with overflowing text in three columns

| first | second | third |

| -- | :--------: | -- |

| this should be a small, compact column | this should be a wide column | this column should also be small and compact, much like the first column || first | second | third |

|---|---|---|

| this should be a small, compact column | this should be a wide column | this column should also be small and compact, much like the first column |

R Markdown tables

If you are using R Markdown, then you can generate a table from

packages like {knitr} or {gt}, but make sure to use

results = 'asis' in your chunk option:

MARKDOWN

```{r fruits-table, results = 'asis'}

dat <- data.frame(

stringsAsFactors = FALSE,

fruit = c("apple", "pear", "orange", "gum gum fruit"),

color = c("🔴", "🟢", "🟠", "🟣"),

price = c("$2.05", "$1.37", "$3.09", "$999.99"),

description = c("a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day",

"a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon",

"a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days",

"a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers")

)

knitr::kable(dat,

format = "pipe",

align = "lcrl",

caption = "Four fruits with color, price in imaginary dollars, and description")

```| fruit | color | price | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| apple | 🔴 | $2.05 | a short, round-ish red fruit that is slightly tapered at one end. It tastes sweet and crisp like a fall day |

| pear | 🟢 | $1.37 | a bell-shaped green fruit whose taste is sweet and mealy like a cold winter afternoon |

| orange | 🟠 | $3.09 | a round orange fruit with a dimply skin-like peel that you must remove before eating. It tastes of sweet and sour lazy summer days |

| gum gum fruit | 🟣 | $999.99 | a round purple fruit with complex swirls along its skin. It is said to taste terrible and give you mysterious powers |

Links

To include links to outside resources in your lesson, you write them

with standard

markdown syntax:

[descriptive link text](https://example.com/link-url). One

thing to remember when writing links (in markdown or anywhere) is that

link

text should make sense out of context. If you find that the link URL

you are using is long, or you want to reuse it multiple times, you can

use a link anchor with the following syntax:

MARKDOWN

This is an example of a [link reference].

I have a long sentence that also has [a link with a long url][long-url-link], so I will use a link reference.

<!-- Collect your link references at the bottom of your document -->

[link reference]: https://example.com/link-reference

[long-url-link]: https://example.com/long-url-is-loooooooooooooooooooooooooongIf you have a link that you want to use across your lesson (e.g. you

have a source for a data set that you want to refer to), then you can

place a link inside a separate file at the top of your lesson repository

called links.md.

Internal Links

When working on a lesson in The Workbench, you do not need to think about what link the website will generate once it’s built in order to write a link to different elements in the lesson. This is important because when you write links relative to your source files, these links will be predictable in any context and allow you to easily detect when filenames change.

To reference other markdown files within the same lesson, use

relative paths from the current file. For example, you will

commonly want to refer learners to the setup

page from within the episodes. To link back to the setup page, you

can use: [setup page](../learners/setup.md) and {sandpaper}

will convert that link to the appropriate format for the lesson

website.

By that same rule, here is how you would write the following links in this episode:

MARKDOWN

- [another episode (e.g. introduction)](introduction.md)

- [the home page](../index.md)

- [the setup page](../learners/setup.md)

- [the "line length" section in the style guide](../learners/style.md#line-length)- another episode (e.g. introduction)

- the home page

- the setup page

- the “line length” section in the style guide

But It Works!

You want to create a link from the style guide in the learners folder to this section on links. All of the links below will work with The Carpentries Workbench, but which one is guaranteed to work and why?

[internal links](https://carpentries.github.io/sandpaper-docs/episodes.html#internal-links)[internal links](episodes.html#internal-links)[internal links](../episodes/episodes.Rmd#internal-links)[internal links](../episodes/episodes.md#internal-links)[internal links](episodes#internal-links)

Think about which files actually exist before the lesson is built.

The answer is 3:

[internal links](../episodes/episodes.Rmd#internal-links)

produces internal links

incorrect solutions

The reasons the others were incorrect is:

- this produces a full static URL, but the URL could easily change (for example, when there is a translation or a fork of this lesson).

- this produces a relative link to the URL, but this can change if the

folder structure of the rendered website changes (e.g. it becomes

episodes/index.html). - this is the correct choice, see above.

- the file extension is incorrect. This episode is written in

R Markdown and needs the

Rmdfile extension. - this is ambiguous, but it is similar to number 2, where it’s

providing a relative link to a URL. This only works on GitHub,

where the

.htmlextension is optional.

Figures

To include figures, place them in the episodes/fig

folder and reference them directly like so using standard markdown

format, with one twist: add an alt attribute at the end to

make it accessible like this:

{alt='alt text'}.

MARKDOWN

{alt="blue

hexagon with The Carpentries logo in white and text: 'The Carpentries'"}Accessibility Point: Alternative Text (aka alt-text)

Alternative text (alt text) is a very important tool for making lessons accessible. If you are unfamiliar with alt text for images, this primer on alt text gives a good rundown of what alt text is and why it matters. In short, alt text provides a short description of an image that can take the place of an image if it is missing or the user is unable to see it.

How long should alt text be?

Alt text is a wonderful accessibility tool that gives a description of an image when it can not be perceived visually. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words, but alt text likely should not be so long, so how long should it be? That depends on the context. Generally, if a figure is of minor importance, then try to constrain it to about the length of a tweet (~150-280 characters) or it will get too descriptive, otherwise, describe the salient points that the reader should understand from the figure.

Wrapping Alt Text lines

You will rarely have alt text that fits under 100 characters, so you can wrap alt text like you would any markdown paragraph:

MARKDOWN

{alt='This is just an icebox

with no plums

which you were probably

saving

for breakfast'}When missing, the image will appear visually as a broken image icon, but the alt text describes what the image was.

If your lesson uses R, some images will be auto-generated from

evaluated code chunks and linked. You can use fig.alt to

include alt text. This blogpost

has more information about including alt text in RMarkdown

documents. In addition, you can also use fig.cap to

provide a caption that puts the picture into context (but take care to

not be redundant; screen readers will read both fields).

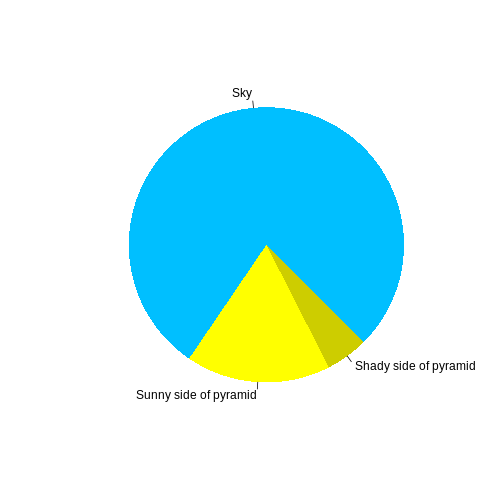

R

pie(

c(Sky = 78, "Sunny side of pyramid" = 17, "Shady side of pyramid" = 5),

init.angle = 315,

col = c("deepskyblue", "yellow", "yellow3"),

border = FALSE

)

Math

One of our episodes contains \(\LaTeX\) equations when describing how to create dynamic reports with {knitr}, so we now use mathjax to describe this:

$\alpha = \dfrac{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}$ becomes: \(\alpha = \dfrac{1}{(1 - \beta)^2}\)

Cool, right?

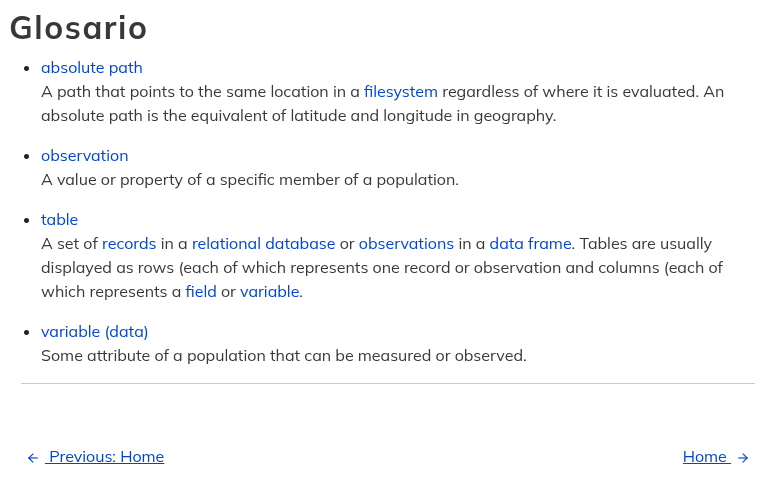

Glosario Terms

Glosario is the Carpentries data science glossary that is developed by the international community, providing terms, definitions and translations to make lessons more accessible.

{sandpaper} can automatically generate glossary links in lessons from links to Glosario terms in lesson content markdown.

Configuration

Firstly, to enable this behaviour, the glosario key

needs to be added to a lesson’s config.yaml.

For automatic retrieval of the latest glossary.yml from

Glosario’s GitHub repository, set:

For manual retrieval from a local (e.g. working on your lesson offline) or remote location (e.g. providing a specific Glosario version), supply a string relative/absolute path or URL to the config:

Lesson content

A lesson maintainer/contributor can add placeholders into the main content of lessons that sandpaper will subsequently process.

Sandpaper understands links to Glosario terms in two ways, either a template-style term, or a hard link to the term page, i.e.:

{{ glosario.<term> }}[<term>](https://glosario.carpentries.org/en/#<term>)

Automatic language selection

When using the template-style term, sandpaper will automatically

generate the URL link using the language specified in the

config.yaml lang setting.

When using the markdown link style, sandpaper will automatically

replace the en/ in the link with the language specified in

the config.yaml lang setting.

For example, if the config.yaml language is set to

lang: de:

[data_structure](https://glosario.carpentries.org/en/#data_structure)

will be replaced with:

[data_structure](https://glosario.carpentries.org/de/#data_structure)

If the term is not available in that language, a warning will be printed when the lesson builds, and it will default back to English.

Example output

To look at a specific example, the datacarpentry/spreadsheet-ecology-lesson can be edited to include Glosario links.

To add a glosario link to the term data structure at the

URL https://glosario.carpentries.org/en/#data_structure,

the markdown becomes:

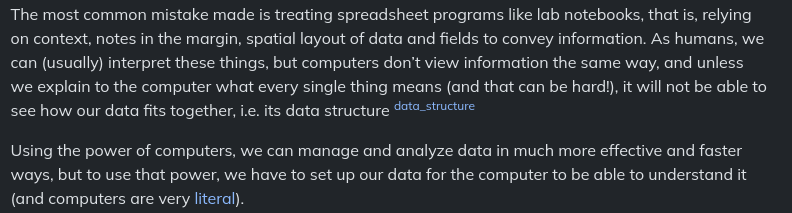

The most common mistake made is treating spreadsheet programs like lab notebooks, that is, relying on context,

notes in the margin, spatial layout of data and fields to convey information. As humans, we can (usually) interpret

these things, but computers don't view information the same way, and unless we explain to the computer what

every single thing means (and that can be hard!), it will not be able to see how our data fits together. This is called

the data structure {{ glosario.data_structure }}.Similarly, to add a link using the inline markdown link syntax, the markdown becomes:

Using the power of computers, we can manage and analyze data in much more effective and faster ways, but to

use that power, we have to set up our data for the computer to be able to understand it

(and computers are very [literal](https://glosario.carpentries.org/en/#literal)).Once the lesson is built, this will produce the following output:

In the first example, {{ glosario.data_structure }} adds

a data_structure link as a superscript inline.

In the second example, a typical markdown link will be inserted.

In either case, sandpaper will find these links and add them to the

global reference.md page in your lesson, built as

reference.html, and linked in the top lesson menu as

Glossary:

Unavailable terms

Users will receive a warning when using terms that are not in the currently selected config.yaml language for the lesson:

- Use

.Rmdfiles for lessons even if you don’t need to generate any code - Run

sandpaper::check_lesson()to identify any issues with your lesson - Run

sandpaper::build_lesson()to preview your lesson locally

The designation of “episode” will likely change. Throught UX testing, it’s clear that calling these lesson units “episodes” is confusing, even for people who have been in The Carpentries for several years. The current working proposal is to call these “chapters”.↩︎

Do not worry if you aren’t comfortable yet, that’s what we will show you in this episode!↩︎

Captions allow visually impaired users to choose if they want to skip over the table contents if it is scannable. For more information, you can read MDN docs: adding a caption to your table↩︎